In a tale filled with greed, envy, unfulfilled promises, and years of legal scheming, Marvel announced a financial settlement on April 28, 2005, with its most famous employee – comic book legend Stan Lee.

Filed under the heading, “Things No One Ever Expected,” Lee had sued Marvel three years earlier for not fulfilling the terms of his employment contract. The subsequent legal maneuvering created a tense situation for Lee and a public relations headache for the company he had helped build.

The beguiling battle began in late October 2002, when the popular CBS news program 60 Minutes II aired a segment about the state of comic books and the tremendous popularity of superhero films. The report also examined Lee’s potential skirmish with Marvel regarding language in his contract, specifically certain payments Lee justly deserved based on the surging box office returns of Marvel films after decades of mediocre efforts and failed attempts at bringing the company’s superheroes to the screen.

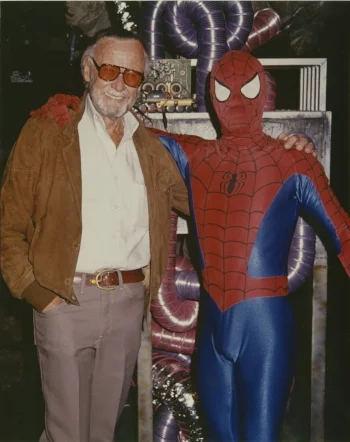

The new program painted Marvel in an evil light – a greedy corporation making insane amounts of money off the backs of its writers and artists. Lee’s 1998 contract seemed straightforward, but when it was inked no one expected the future to include such wildly successful films – X-Men (2000) earned nearly $300 million worldwide, while Spider-Man (2002) became a global phenomenon, drawing some $821 million.

60 Minutes II correspondent Bob Simon, using a bit of spicy language that seemed uncharacteristic for the venerable CBS show, actually asked Lee if he felt “screwed” by Marvel. Lee toned down his usual bombast though and displayed remorse for having to sue his employer, a situation that he explained “I try not to think of it.” As a result, many Marvel fans sided with Lee in the dispute.

Mere days after the segment aired, Lee sued Marvel for not honoring a stipulation that promised to pay him 10 percent of the profits from Marvel Enterprise film and television productions. Despite his $1 million annual salary as chairman emeritus, Lee’s attorney’s argued that the provision be honored. The grand battle between Marvel and its most famous employee shocked observers and sparked news headlines around the globe. Summing up the public’s general feeling about the controversy, Brent Staples of the New York Times explained: “You can’t blame the pitchman for standing firm and insisting on his due.”

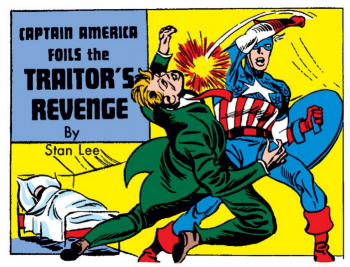

The public nature of the contract and its terms (including his hefty salary for a mere 15 hours of work each week, guaranteed first-class travel, and hefty pension payouts to Lee’s wife Joanie and daughter J.C.) led some comic book insiders to once again dredge up the argument regarding how the comic book artists and co-creators – most notably Jack Kirby – were treated by Marvel (and by extension Lee). Rehashing this notion and the idea that Lee attempted to capitalize off the success of the films turned some people against him. To critics, Lee got rich, while Kirby and others didn’t. The injustice had been done and they weren’t going to change their opinions, regardless of what Lee’s contract stipulated

In early 2005, after the judge presiding over the case ruled in Lee’s favor, he again appeared on 60 Minutes. “It was very emotional,” said Lee. “I guess what happened was I was really hurt. We had always had this great relationship, the company and me. I felt I was a part of it.” Despite the high profile nature of the lawsuit and its apparent newsworthiness, Marvel attempted to bury the settlement agreement with Lee in a quarterly earnings press release.

In April 2005, Marvel announced that it had settled with Lee, suggesting that the payoff cost the company $10 million. Of course, the idea that Lee had to sue the company that he spent his life working for and crisscrossing the globe promoting gave journalists the attention-grabbing headline they needed. And, while the settlement amount seemed grandiose, it was a pittance from the first Spider-Man film alone, which netted Marvel some $150 million in merchandising and licensing fees.

Despite the financial loss, the lawsuit resulted in an unexpected upside for Marvel. The settlement put in motion plans for the company to produce its own movies, a major shift in policy. Since the early 1960s, Marvel and its predecessor companies had licensed its superheroes to other production companies. Back then, the strategy allowed Marvel to outsource the risk involved with making television shows and films, but also severely hindered it from profiting from the creations. This move gave Marvel control, not only of the films themselves, but the future cable television and video products that would generate revenues.

Merrill Lynch & Co extended a $525 million credit line for Marvel to launch the venture (using limited rights to 10 Marvel characters as collateral), and Paramount Pictures signed an eight-year deal to distribute up to 10 films, including fronting marketing and advertising costs.

Interestingly, the details of the settlement between Lee and his lifelong employer shed light on suspect Hollywood accounting practices that film companies use to artificially reduce profitability. For example, for all the successes Marvel films had in the early 2000s, raking in some $2 billion in revenues between 2000-2005, Marvel’s cut for licensing equaled about $50 million. Despite his earlier contract with the company, Lee had received no royalties.

Although Lee received the settlement money and fences were eventually mended at Marvel, the episode is one of the stranger ones in Lee’s long career. In the long run, it transformed Marvel’s film strategy and helped it become a movie powerhouse.