Stan Lee would have turned 101-years old on December 28. This essay looks at his extraordinary life and how he led Marvel, becoming a pop culture icon in the process.

Read moreSTANLEY LIEBER BECOMES STAN LEE AND "MR. TIMELY COMICS"

How Does Stan Lee Get into Comic Books? A Stroke of Luck or Something Else?

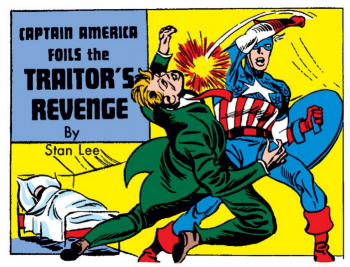

Stanley Lieber uses the pseudonym “Stan Lee” in his first published story!

Rising up to his feet and towering over a messy desktop with drawings strewn haphazardly about and correspondence littering every square inch, Timely Comics head writer and editorial director Joe Simon reached out his hand to welcome his new young assistant. Cigar smoke is thick in the room as Simon’s big hand comes at the teenager sitting in front of him.

Still a little dizzy from getting the job, Stanley Leiber vigorously pumped the older man’s hand – A steady paycheck…He would make eight dollars a week! He had recently graduated from high school, the DeWitt Clinton Class of 1939.

For a young man struggling to find full-time work, the pay meant that he might help the family regain its footing. They had been reeling since his father Jack couldn’t find work in the dressmaking industry throughout the tough years of the Great Depression. The job gave the teenager security and a shot to prove himself in writing and publishing. Words appealed to the boy—always had.

Stanley dreamed of one day writing the Great American Novel.

But in this new job, Stanley had to start at the bottom. He plied away as an office boy for Simon and the other full-time Timely Comics employee – artist and writer Jack Kirby. Little more than an assistant, some days he refilled Kirby and Simon’s inkwells. He had the mammoth task to get the two men sandwiches while the duo concocted new superhero stories.

Lieber worked with enthusiasm, even if he spent hours sweeping floors or erasing stray pencil marks on finished pages to prep them for publication. The youngster achieved his primary goal – simply finding a permanent position. He watched and learned from two of the industry’s budding stars.

More importantly, Stanley had a job! His father’s fate would not befall him. He set off on a career.

The Timely Job at Timely Comics…And a Mystery!

Many episodes in Stanley’s early life are shrouded in uncertainty. How the teenager bounded from Clinton High School to Simon and Kirby’s assistant at Timely involves both a bit of mystery and a touch of mythmaking.

There are several versions of his Timely Comics origin story. One account begins with his mother Celia. Clearly she put her hopes in her oldest son, particularly since her faith in her husband nearly led the family to ruin.

Here we have Celia telling Stanley about a job opening at a publishing company where her brother Robbie worked. Without delay, the young high school grad shows up at the McGraw-Hill building on West 42nd Street, but knows little about the company or comic books. With Robbie’s prodding, Simon explains the business and how comic books are made. He then offers the teen a job. Basically, he and Kirby are so frantic and overworked, particularly with their new hit Captain America, that they just need someone (anyone, really) to provide an extra set of hands.

Robbie Solomon is also at the center of a different account (here the main player), essentially a conduit between Simon and owner Martin Goodman. In addition to being Celia Lieber’s brother, Robbie married the publisher’s sister Sylvia. Goodman surrounded himself with family members, despite the imperious tone he took with everyone who worked for him. Receiving Robbie’s stamp of approval (and the familial tie) made the boy’s hire fait accompli. Simon, then, despite what he may or may not have thought of the boy, basically had to take Leiber on. “His entire publishing empire was a family business,” explained historians Blake Bell and Michael J. Vassallo. Solomon had a strange job – a kind of in-house spy who ratted out employees not working hard enough or playing fast and loose with company rules.

While the family connection tale is credible and plays into the general narrative of Goodman’s extensive nepotism, Lee offered a different perspective, making it more of a coincidence. “I was fresh out of high school,” he recalled, “I wanted to get into the publishing business, if I could.” Rather than being led by Robbie, Lee explained: “There was an ad in the paper that said, ‘Assistant Wanted in a Publishing House.’” This alternative version calls into question Lee’s early move into publishing – and throwing up for grabs the date as either 1940, which is usually listed as the year of his hiring, or 1939, as he later implied.

Lieber may have not known much about comic books, but he recognized publishing as a viable option for someone with his skills. He knew that he could write, but had no way of really gauging his creative talents. Although Goodman was a cousin by marriage, he did not have much interaction with his younger relative, so it wasn’t as if Goodman purposely brought Lieber into the firm. No one will ever really know how much of a wink and nod Solomon gave Simon or if Goodman even knew about the hiring, though the kid remembered the publisher being surprised the first time he saw him in the building.

The teen, though bright, talented, and hard working, needed a break. His early tenure at Timely Comics served as a kind of extended apprenticeship or on-the-job training at comic book university. Lieber was earnest in learning from Simon and Kirby as they scrambled to create content. Since they were known for working fast, the teen witnessed firsthand how two of the industry’s greatest talents functioned. The lessons he learned set the foundation for his own career as a writer and editor, as well as a manager of other highly talented individuals.

Stan Lee: A Life, by award-winning historian Bob Batchelor

Happy 100th Birthday Celebration for Marvel Legend Stan Lee

Stan Lee as Artist and Producer — The Man “Behind” Marvel’s Success

Stan Lee: A Life by cultural historian Bob Batchelor

Stan Lee had been working in the comic book industry for decades before the successes of the 1960s. Lee’s most important lessons from those first two-plus decades in comic book publishing were about how to manage a business, the seemingly simple on paper, but difficult in practice nature of running a company.

Comic book publishing was not for the meek – governed by relentless deadlines in an era before technology made many of the processes more efficient. While not trained in business, Lee became a manager, which gave him insider perspective into the machinations of the industry, particularly in contrast to the artist or writer view that is solely on their specific creation. From an enterprise perspective, Lee learned everything that would enable him to re-launch Marvel in the early 1960s, ultimately overseeing the company as it became a force in comic books and later, American popular culture as a whole.

Yet, if we were just discussing Lee as an editor and manager of Marvel, the story would be truncated. Of course, he was also a creator, as were so many of the early comic book artists and writers, more or less forced into developing managerial acumen, because, well someone had to run the business side. What emerged in Lee as a result of the melding of the business and creative parts of his work life was a keen sense of responsibility. He had to nurture the artistic aspects of comic book creation, from writing and editing to assigning cover art and lettering, while also overseeing the business side, from managing budgets to working with the production team to ensure deadlines were met in an industry with slim margin for error. Ultimately, all responsibility wrapped back to Lee.

Rather than these viewpoints warring inside Lee as he built his career, he used them as a way to create a central worldview: Comic books were important as tools to educate. They had value for readers – regardless of age – as a means of education, including outlining a value system based on the complexity of the human experience, not unlike literature and poetry. Lee realized that this perspective stood in contrast to the mainstream opinion that comic books were “pulp,” simple stories aimed at children and feeble-minded adults (a common belief through the 1960s).

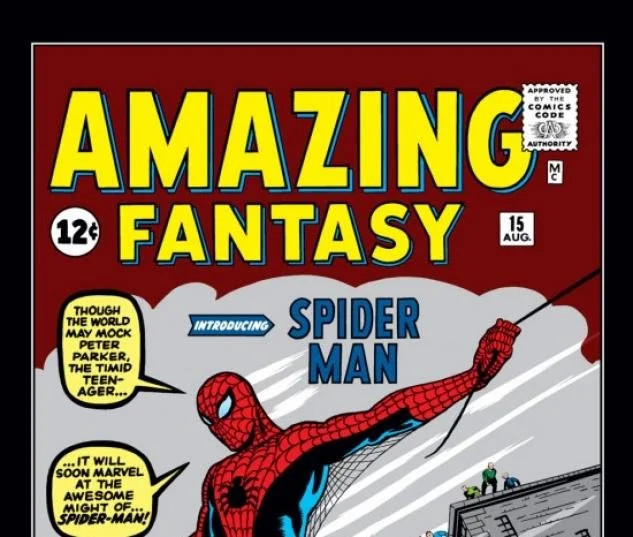

Without going into deep analysis of the controversial creation of Spider-man – an amalgamation of the thinking and experiences lived by Lee, Steve Ditko, Jack Kirby – the character’s popularity provided Lee with an instrument to explore his ideas about how important comic books could be as tool for education. Spider-man gave him influence and proved that he could help shape culture in ways unimaginable during the first 20 years of his career.

Continually attempting to establish Marvel as different, Lee started calling the company the “House of Ideas,” which stuck with journalists and became part of the company’s cachet. If a downside existed in the surge of Marvel comics into the public consciousness it is that Lee and his bullpen teammates had to balance between entertainment, social issues, and profitability. Stan valued the joy derived from reading comics, but he wanted them to be useful: “Hopefully I can make them enjoyable and also beneficial…This is a difficult trick, but I try within the limits of my own talent.” Lee wanted to have it both ways – for people to read the books as entertainment, but also be taken seriously.

“Hopefully I can make them enjoyable and also beneficial…This is a difficult trick, but I try within the limits of my own talent.”

At the same time, Marvel had to sell comics, which meant that little kids and young teenagers drove a sizeable chunk of the market. In 1970, Lee estimated that 60 percent of Marvel’s readers were under 16-years old. The remaining adult readership was enormous given historical numbers, but kept Lee focused on the larger demographic. “We’re still a business,” he told an interviewer. “It doesn’t do us any good to put out stuff we like if the books don’t sell…I would gain nothing by not doing things to reach the kids, because I would lose my job and we’d go out of business.”

On one hand, the industry moved so quickly that Lee and his creative teams constantly fought to get issues out on time. The number of titles Marvel put out meant that everyone had to be constantly producing. So, when Lee was in the office or working from home, he committed to getting content out. Roy Thomas recalls, “Stan and I were editing everything, and the writers were editing what they did, and we had a few assistant editors that didn't really have any authority...that was about it.” However, that chaotic atmosphere made it rife for animosities to form or fester. Lee needed content out the door and Goodman tried to maintain control over cover artwork and other little details that inevitably slowed down the process.

Thomas’ ascension and Lee’s pull toward management did shift the editorial direction, if for no other reason than that Stan wouldn’t be writing full-time any longer. “It was time to kind of branch out a little bit,” Thomas explained. “We wanted to keep some of that Marvel magic, and at the same time, there had to be room for other art styles and other writing styles.” The most overt change came when Lee turned in the copy for The Amazing Spider-Man #110. The late 1971 issue was the last Lee wrote for the character. Writer Gerry Conway succeeded Lee and the next books in the series would be co-created by Conway and star artist John Romita.

While many adults looked down on Lee for writing comic books, especially early in his career, he developed a masterful style that rivals or mirrors those of contemporary novelists. Lee explained:

Every character I write is really me, in some way or other. Even the villains. Now I’m not implying that I’m in any way a villainous person. Oh, perish forbid! But how can anyone write a believable villain without thinking, “How would I act if he (or she) were me? What would I do if I were trying to conquer the world, or jaywalk across the street?...What would I say if I were the one threatening Spider-Man? See what I mean? No other way to do it.”

Lee’s distinctive voice captured the essence of his chosen medium.

Lee also understood that the meaning of success in contemporary pop culture necessitated that he embrace the burgeoning celebrity culture. If a generation of teen and college-aged readers hoped to shape him into their leader, Lee would gladly accept the mantle, becoming their gonzo king. Fashioning this image in a lecture circuit that took him around the nation, as well as within the pages of Marvel’s books, Lee created a persona larger than his publisher or employer. As a result, he transformed the comic book industry.

Unlike Bob Dylan or Jann Wenner, for example, Stan didn’t plan this revolution. He didn’t say to himself that he would cocreate a character that would become part of American folklore. It wasn’t planned, yet it seems completely intentional.

Baby boomers grew up with Stan’s voice in their heads. Interestingly, Lee spoke for Marvel’s superheroes to eager audiences talking about the characters, while at the same time creating the dialogue in the actual comics. So he was the person talking about the characters he himself was voicing. In addition, he wasn’t just in the media; Stan was talking directly to readers within the pages. He was Spider-Man’s voice, while also talking about the comics, the company, his colleagues, and the world to a captivated audience.

By the time Gen Xers started reading comics, Marvel’s style was wholly entrenched. As each generation ages out of traditional comic book reading age, Lee’s voice becomes commensurate with nostalgia—a part of our lives we look back to with fondness and equate with better times. Immersed in a heavily capitalistic, entertainment-driven culture, embedded stories are ones that get retold, and Marvel superheroes become a balm for a cultural explosion driven by cable television, global box office calculations, and the web. In what seems like the blink of an eye, the Marvel voice became the voice of modern storytelling.

Why did the Marvel Universe come to dominate global popular culture? Largely based on Stan supplying a voice to a mythology. Certainly, the creation of the Marvel Universe was a team effort, like all forms of entertainment, nothing is created in a vacuum. There are unheralded people in the process and those who deserve as much credit as Lee for their roles. Yet, it was the unmistakable “music” that Lee conceived that launched a cultural revolution.

Crisscrossing the nation while speaking at college campuses, sitting for interviews, and conversing with readers in the “Stan’s Soapbox” pages in the back of comic books, Lee paved the way for intense fandom. His work gave readers a way to engage with Marvel and rejoice in the joyful act of being a fan. Geek/nerd culture began with “Smiley” and his Merry Marauding Bullpen nodding and winking at fans each issue. Lee’s commitment to building a fan base took fandom beyond sales figures and consumerism to authentically creating communities. The Marvel Cinematic Universe has spun this idea into global proportions. It is the fans of the MCU across film and television that has reinforced and spread Stan’s voice across the world.

Amazing Fantasy #15, the comic that launched Spider-Man into the popular culture stratosphere

The superheroes that Lee and his co-creators brought to life in Marvel comic books remain at the heart of contemporary storytelling. Lee created a narrative foundation that has fueled pop culture across all media for nearly six decades.

By establishing the voice of Marvel superheroes and shepherding the comic books to life as the creative head of Marvel, Lee cemented his place in American history. According to analyst Paul Dergarabedian, the results have been breathtaking: “The profound impact of Stan Lee’s creations and the influence that his singular vision has had on our culture and the world of cinema is almost immeasurable and virtually unparalleled by any other modern day artist.”

“The profound impact of Stan Lee’s creations and the influence that his singular vision has had on our culture and the world of cinema is almost immeasurable and virtually unparalleled by any other modern day artist.”

Stan Lee Spreads the Gospel of Marvel Comic Books

Although Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four revolutionized the comic book industry, Stan Lee still felt the sting of working in a third-class business at a time when most adults thought comic books were aimed at children. What Lee realized, though, was that college students in the 1960s and 1970s were responding to Marvel in a new way — gleefully reading and re-reading the otherwordly antics of the costumed heroes.

Read more30% Discount on Stan Lee: A Life by Cultural Historian Bob Batchelor

Stan Lee: A Life is the epic tale of one of the world’s most important creative icons. With Spider-Man, the Avengers, Black Panther, and countless other Marvel superheroes he co-created, Stan introduced heroes that were complex and fallible – just like all of us. Championing Marvel for parts of ten decades, Lee revolutionized global culture.

Read moreStan Lee: A Life Well-Lived -- Excelsior!

“Lee became Marvel madman, mouthpiece, and all-around maestro – the face of comic books for six decades. The man who wanted to pen the Great American Novel did so much more. Without question, Lee became one of the most important creative icons in contemporary American history.”

— Bob Batchelor, author, Stan Lee: The Man Behind Marvel

Read more5 Reasons to Love Stan Lee

Stan Lee’s birthday on December 28 gave fans a reason to contemplate his place among the world’s most significant creative icons. It is easy to argue that the ideas Lee and his co-creators brought to life in Marvel superhero comic books are at the heart of contemporary storytelling.

Lee created a narrative foundation that has fueled pop culture for nearly six decades. While countless shelves have been filled with books about comic book history and those responsible for originating this uniquely American form of mass communication, there are still many reasons to examine Lee’s specific role.

Lee created a narrative foundation that has fueled pop culture for nearly six decades.

History and context are important in helping people comprehend their worlds. New comic book readers and ardent filmgoers who turn out in droves to see Marvel Universe films should grasp how these influences impact their worldviews.

Here are five reasons to love Stan Lee:

5. Fandom

In the 1960s and 1970s, no matter the tiny hamlet, thriving city, or rural enclave, if a kid got their hands on a Marvel comic book, they knew that they had a friend in New York City named Stan Lee. Each month, like magic, Lee and the Mighty Marvel Bullpen put these colorful gifts into our hands (in my youth in the 1970s, showcasing the ever-present “Stan Lee Presents” banner), which enabled us to travel the galaxies along with Thor, Iron Man, the Avengers, and X-Men.

Crisscrossing the nation speaking at college campuses, sitting for interviews, and speaking to readers in the “Stan’s Soapbox” pages in the back of comic books, Lee paved the way for intense fandom. His work gave readers a way to engage with Marvel and rejoice in the joyful act of being a fan. Geek/nerd culture began with “Smilin’ Stan” and his Merry Marauding Bullpen nodding and winking at fans each issue. Lee’s commitment to building a fan base took fandom beyond capitalistic sales figures and consumerism to creating communities.

4. Vision

While many comic book experts and insiders worried about monthly sales figures and demographics, Lee understood that Marvel’s horde of superheroes could form the basis of a multimedia empire. Ironically, he talked about turning Marvel into the next Disney decades before Walt’s company gobbled up the superhero shop. Back then, Lee’s idea drew derision and people openly scoffed at such a notion.

Lee saw the pieces of a multimedia empire and relentlessly pursued this vision, almost singlehandedly pushing Marvel as a film and television company. Lee championed superhero films and television shows in the mid-1960s and through the 1970s when Hollywood producers couldn’t fathom someone like Spider-man, Thor, or Iron Man appealing to a mass audience. It took Star Wars and Christopher Reeves’s Superman to show Tinseltown what movies could be.

3. Leadership

One of the most important aspects of creating comic books is that the process requires all-encompassing teamwork, from plot creation through distribution. While a great deal of work takes place alone, like an inker working page-by-page, much of the effort is coordinated and intricate.

At Marvel, really from the time Lee took over as editor as a teenager in 1941 until the boom in the early 1960s, he managed the artistic and production aspects of the company, simultaneously serving as art director, chief editor, and head writer. Much of the scholarly and critical commentary has centered on the controversy regarding Lee’s role as creator or co-creator of the iconic superheroes, but without similar focus or discussion about how he managed these other aspects. Artists Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko were phenomenal talents, but in contrast to Lee, they focused on one part of the production process. Lee directed, managed, or supervised it all.

2. Tenacity

In the early 1960s, most people looked down on the comic book industry and the creative teams that produced comics. Suffering from bouts of frustration and despair, Lee couldn’t stomach working in comics any longer. He warred with the idea of chucking his more than 20-year career versus bringing home the steady paycheck that Marvel’s mediocrity delivered. “We’re writing nonsense…writing trash,” he told his wife Joan. I want to quit, he confided: “After all these years, I’m not getting anywhere. It’s a stupid business for a grownup to be in.”

Yet, when Marvel publisher Martin Goodman suggested he mimic DC and create a superhero team, Lee took a risk on a new kind of team, heroes who had their superpowers foisted on them and didn’t hide from their real human emotions. The Fantastic Four gave Lee the chance to explore a new type of hero and fans responded. Lee didn’t quit. The Marvel Universe was born.

1. Transforming Storytelling

Lee’s legacy is undeniable: he transformed storytelling by introducing generations of readers to flawed heroes who also dealt with life’s everyday challenges, in addition to the treats that could destroy humankind.

Generations of artists, writers, actors, and other creative types have been inspired, moved, or encouraged by the Marvel Universe he gave voice to and birthed. Lee did not invent the imperfect hero, one could argue that such heroes had been around since Homer’s time and even before, but Lee did deliver it – Johnny Appleseed style, a dime or so a pop – to a generation of readers hungry for something new.

The Fantastic Four transformed the kinds of stories comic books could tell. Spider-Man, however, brought the idea home to a global audience. Lee told an interviewer that he had two incredibly instinctive objectives: introduce a superhero “terribly realistic” and one “with whom the reader could relate.” While the nerd-to-hero storyline seems like it must have sprung from the earth fully formed, Lee gave readers a new way of looking at what it meant to be a hero and spun the notion of who might be heroic in a way that spoke to the rapidly expanding number of comic book buyers. Spider-Man’s popularity revealed the attraction to the idea of a tainted hero, but at the same time, the character hit the newsstands at the perfect time, ranging from the growing Baby Boomer generation to the optimism of John F. Kennedy’s Camelot, this confluence of events resulting in a new age for comic books.