Stan Lee as Artist and Producer — The Man “Behind” Marvel’s Success

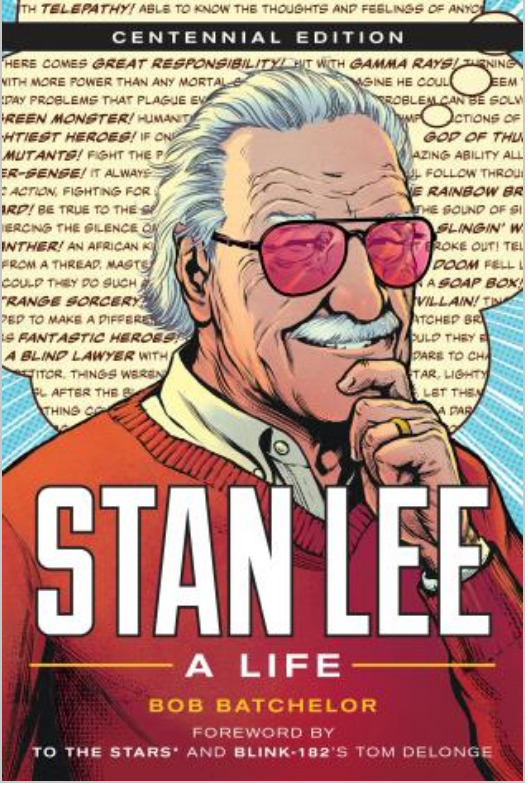

Stan Lee: A Life by cultural historian Bob Batchelor

Stan Lee had been working in the comic book industry for decades before the successes of the 1960s with the Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, and other superheroes. Lee’s most important lessons from those first two-plus decades in comic book publishing were about how to manage a business, seemingly straightforward on paper, but difficult in practice. Unlike leaders today, Lee had to learn how to run a company with no formal training or college background.

Comic book publishing was not for the meek – the industry was governed by relentless deadlines in an era before technology made many of the processes more efficient. Not trained in business, Lee became a manager and supervisor, which gave him insider perspective into the machinations of the industry (he had to watch over the entire process, in contrast to the typical artist or writer perspective, solely on their specific role in creating work). From an enterprise perspective, Lee learned everything that would enable him to re-launch Marvel in the early 1960s, ultimately overseeing the company as it became a force in comic books and later, American pop culture as a whole.

Yet, if we were just discussing Lee as an editor and manager of Marvel, the story would be truncated. Of course, he was also a creator, as were so many of the early comic book artists and writers, more or less forced into developing managerial acumen, because…well someone had to run the business side. Unlike the writers and editors he hired, Lee had an added responsibility to ensure the operation achieved its business goals. As a result, Lee had to meld his creative and managerial roles for the good of the organization. He had to nurture the artistic aspects of comic book creation, from writing and editing to assigning cover art and lettering, while also overseeing the business side, from managing budgets to working with the production team to ensure deadlines were met in an industry with slim margin for error.

Ultimately, all responsibility wrapped back to Lee. His boss—owner Martin Goodman—was not a ruthless business leader, but he did make difficult decisions, like forcing Lee to fire staff when sales dropped (for example, when the industry suffered through Congressional inquiry in the 1950s).

Rather than these viewpoints warring inside Lee as he built his career, he used them as a way to create a central worldview: Comic books were important as tools to educate. They had value for readers as a means of education, including outlining a value system based on the complexity of the human experience, not unlike literature and poetry. Lee realized that this perspective stood in contrast to the mainstream opinion that comic books were “pulp,” simple stories aimed at children and feeble-minded adults (a common belief through the 1960s, which included Goodman).

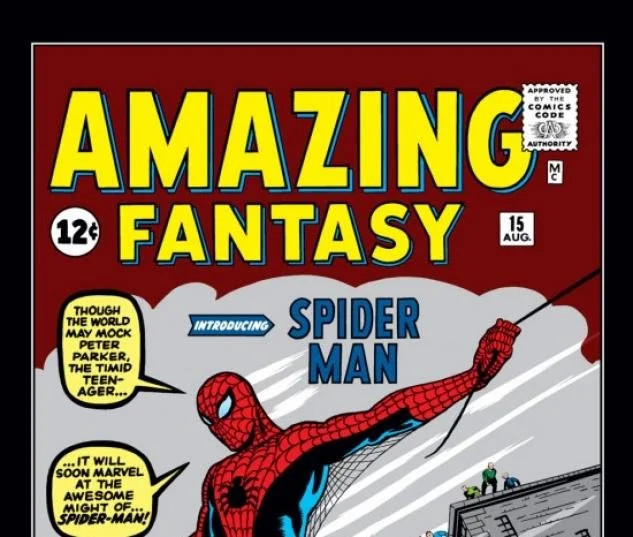

Without going into deep analysis of the controversial creation of Spider-Man – an amalgamation of the thinking and experiences lived by Lee, Steve Ditko, Jack Kirby – the character’s popularity provided Lee with an instrument to explore his ideas about how important comic books could be as tool for education. Spider-Man gave him influence and proved that he could help shape culture in ways unimaginable during the first 20 years of his career.

Continually attempting to establish Marvel as different from its competitors and industry leader DC Comics, Lee started calling the company the “House of Ideas,” which stuck with journalists and became part of the company’s cachet. If a downside existed in the surge of Marvel comics into the public consciousness it is that Lee and his bullpen teammates had to balance between entertainment, social issues, and profitability. Stan valued the joy derived from reading comics, but he wanted them to be useful: “Hopefully I can make them enjoyable and also beneficial…This is a difficult trick, but I try within the limits of my own talent.” Lee wanted to have it both ways – for people to read the books as entertainment, but also be taken seriously by older readers.

“Hopefully I can make them enjoyable and also beneficial…This is a difficult trick, but I try within the limits of my own talent.”

At the same time, Marvel had to sell comics, which meant that little kids and young teenagers drove a sizeable chunk of the market. In 1970, Lee estimated that 60 percent of Marvel’s readers were under 16-years old. The remaining adult readership was enormous given historical numbers, but kept Lee focused on the larger demographic. “We’re still a business,” he told an interviewer. “It doesn’t do us any good to put out stuff we like if the books don’t sell…I would gain nothing by not doing things to reach the kids, because I would lose my job and we’d go out of business.”

The fear inherent in Lee’s voice exemplifies the challenges he faced as a creative and manager. Kirby, Ditko, and other freelancers could put all their effort into creating, but Lee had to ensure the entire operation remained viable. Most comic book historians downplay or overlook this essential point—Lee had to answer to Goodman…and Lee alone. This is the reason comic books and the characters were viewed from a cutthroat perspective. Success equaled sales, anything else was dropped. For example, Hulk lasted few issues in its early run, while Millie the Model sold for decades. Marvel was a business, which Lee had to live and breath in a way his co-creators did not.

On one hand, the industry moved so quickly that Lee and his creative teams constantly fought to get issues out on time. The number of titles Marvel put out meant that everyone had to be constantly producing. So, when Lee was in the office or working from home, he committed to getting content out. Roy Thomas recalls, “Stan and I were editing everything, and the writers were editing what they did, and we had a few assistant editors that didn't really have any authority…that was about it.” However, that chaotic atmosphere made it rife for animosities to form or fester. Lee needed content out the door and Goodman tried to maintain control over cover artwork and other little details that inevitably slowed down the process.

Thomas’ ascension and Lee’s pull toward management did shift the editorial direction, if for no other reason than that Stan wouldn’t be writing full-time any longer. “It was time to kind of branch out a little bit,” Thomas explained. “We wanted to keep some of that Marvel magic, and at the same time, there had to be room for other art styles and other writing styles.” The most overt change came when Lee turned in the copy for The Amazing Spider-Man #110. The late 1971 issue was the last Lee wrote for the character. Writer Gerry Conway succeeded Lee and the next books in the series would be co-created by Conway and star artist John Romita.

While many adults looked down on Lee for writing comic books, especially early in his career, he developed a masterful style that rivals or mirrors those of contemporary novelists. Lee explained:

Every character I write is really me, in some way or other. Even the villains. Now I’m not implying that I’m in any way a villainous person. Oh, perish forbid! But how can anyone write a believable villain without thinking, “How would I act if he (or she) were me? What would I do if I were trying to conquer the world, or jaywalk across the street?...What would I say if I were the one threatening Spider-Man? See what I mean? No other way to do it.”

Lee’s distinctive voice captured the essence of his chosen medium.

Lee also understood that the meaning of success in contemporary pop culture necessitated that he embrace the burgeoning celebrity culture. If a generation of teen and college-aged readers hoped to shape him into their leader, Lee would gladly accept the mantle, becoming their gonzo king. Fashioning this image in a lecture circuit that took him around the nation, as well as within the pages of Marvel’s books, Lee created a persona larger than his publisher or employer. As a result, he transformed the comic book industry.

Unlike Bob Dylan or Jann Wenner, for example, Stan didn’t plan this revolution. He didn’t say to himself that he would co-create a character that would become part of American folklore. It wasn’t planned, yet it seems completely intentional.

Baby Boomers grew up with Stan’s voice in their heads. Interestingly, Lee spoke for Marvel’s superheroes to eager audiences talking about the characters, while at the same time creating the dialogue in the actual comics. In other words, he was the person talking about the characters he himself was voicing. In addition, he wasn’t just in the media; Stan was talking directly to readers within the pages. He was Spider-Man’s voice, while also talking about the comics, the company, his colleagues, and the world to a captivated audience.

By the time Gen Xers started reading comics, Marvel’s style—and Stan’s voice—was wholly entrenched. As each generation aged out of traditional comic book reading age, Lee’s voice then became commensurate with nostalgia—a part of our lives we look back to with fondness and equate with better times. Immersed in a heavily capitalistic, entertainment-driven culture, embedded stories are ones that get retold. Marvel superheroes became a balm for a cultural explosion driven by cable television, global box office calculations, and the web. In what seemed like the blink of an eye, the Marvel voice (i.e. Stan Lee) became the voice of modern storytelling.

Why did the Marvel Universe come to dominate global popular culture? Largely based on Stan supplying a voice to a mythology. Certainly, the creation of the Marvel Universe was a team effort, like all forms of entertainment, nothing is created in a vacuum. There are unheralded people in the process and those who deserve as much credit as Lee for their roles. Yet, it was the unmistakable “music” that Lee conceived that launched a cultural revolution.

Crisscrossing the nation while speaking at college campuses, sitting for interviews, and conversing with readers in the “Stan’s Soapbox” pages in the back of comic books, Lee paved the way for intense fandom. His work gave readers a way to engage with Marvel and rejoice in the joyful act of being a fan. Geek/nerd culture began with “Smiley” and his Merry Marauding Bullpen nodding and winking at fans each issue. Lee’s commitment to building a fan base took fandom beyond sales figures and consumerism to authentically creating communities. The Marvel Cinematic Universe has spun this idea into global proportions. It is the fans of the MCU across film and television that has reinforced and spread Stan’s voice across the world.

Amazing Fantasy #15, the comic that launched Spider-Man into the popular culture stratosphere

The superheroes that Lee and his co-creators brought to life in Marvel comic books remain at the heart of contemporary storytelling. Lee created a narrative foundation that has fueled pop culture across all media for nearly six decades.

By establishing the voice of Marvel superheroes and shepherding the comic books to life as the creative head of Marvel, Lee cemented his place in American history. According to analyst Paul Dergarabedian, the results have been breathtaking: “The profound impact of Stan Lee’s creations and the influence that his singular vision has had on our culture and the world of cinema is almost immeasurable and virtually unparalleled by any other modern day artist.”

“The profound impact of Stan Lee’s creations and the influence that his singular vision has had on our culture and the world of cinema is almost immeasurable and virtually unparalleled by any other modern day artist.”

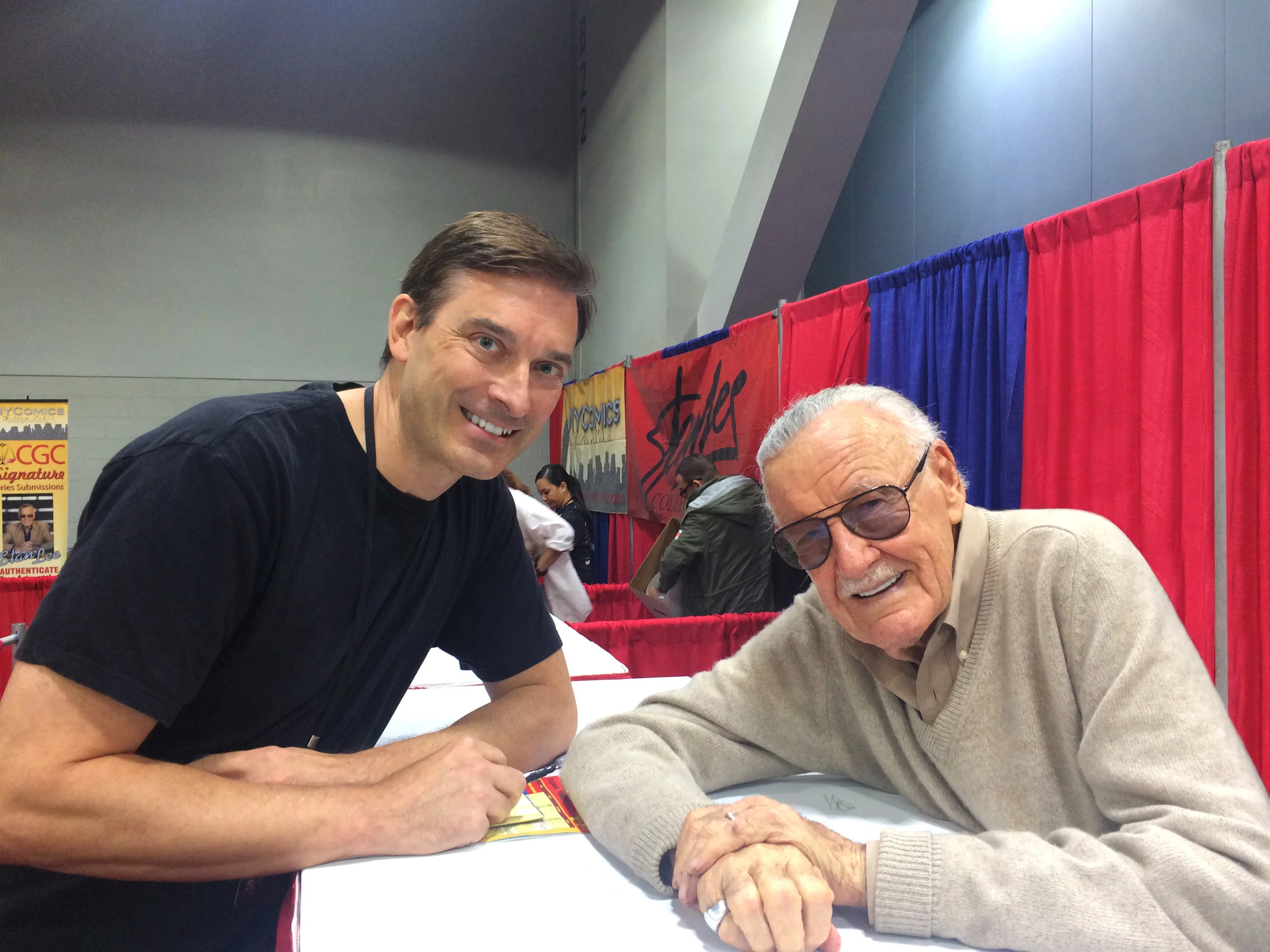

Cultural Historian and Biographer Bob Batchelor with Stan Lee