In The Gatsby Code, cultural historian Bob Batchelor—award-winning author of acclaimed biographies and expert on American mythmaking—offers a masterful deep dive into one of literature’s most enduring icons: Jay Gatsby. As The Great Gatsby turns 100, Batchelor delivers a revelatory chronicle of the novel’s past, present, and future impact, weaving cultural history, literary analysis, and philosophical inquiry into a riveting exploration of why Gatsby still matters.

Read more3 REASONS YOUNG PROFESSIONALS SHOULD READ THE AUTHENTIC LEADER

The workplace is undergoing constant change. As a result, young professionals are stepping into roles that demand adaptability, resilience, and a strong sense of purpose. This type of people-first leadership is at the heart of authentic leadership.

The Authentic Leader: The Power of Deep Leadership in Work and Life is a guide for anyone who aspires to lead with integrity and impact, no matter what stage they are at in their career stage. Here’s why young professionals should read this book and the lessons they’ll take away.

1. Leadership Starts Before the Title

Many young professionals assume leadership begins with a promotion, but The Authentic Leader teaches that leadership is a mindset, not a job title. Leadership starts with self-awareness, responsibility, and the ability to positively influence others—whether you’re managing a team or contributing as an individual.

Lesson Learned: Great leaders take ownership of their work, build trust, and inspire those around them long before they reach the executive suite. By embracing leadership principles early, young professionals set themselves apart and create additional opportunities for growth.

2. Authenticity Builds Long-Term Success

In a world that rewards personal branding and social media presence, it is easy to fall into the trap of trying to be who you think others want you to be. The Authentic Leader emphasizes that real success comes from being authentic, aligning your values with your work, and building trust through transparency.

Lesson Learned: The strongest leaders—now and throughout history—have been those who remain true to their values, communicate honestly, and foster real connections. Young professionals who develop these habits early will build lasting credibility and meaningful careers.

3. Emotional Intelligence is the Key to Influence

The workplace is filled with diverse perspectives, challenges, and moments of uncertainty. The Authentic Leader highlights the power of emotional intelligence in navigating relationships, resolving conflicts, and creating positive workplace cultures.

Lesson Learned: Young professionals who practice empathy, active listening, and emotional self-awareness will be better equipped to collaborate, lead, and create a lasting impact in their industries.

Final Thought

Leadership isn’t something you wait for over days, months, and years. It is your responsibility to develop the necessary skills every day. The Authentic Leader provides the tools and insights young professionals need to become confident, purpose-driven leaders in a fast-changing world. By understanding these principles early, they can build careers that are not only successful, but also deeply fulfilling.

Are you ready to take the first step toward authentic leadership? Pick up The Authentic Leader and start shaping your leadership journey today.

The Authentic Leader by Bob Batchelor

THE AUTHENTIC LEADER: FAQs

The Authentic Leader: The Power of Deep Leadership in Work and Life by award-winning cultural historian and biographer Bob Batchelor explores the concept of deep leadership, which emphasizes authenticity, transparency, and empathy in the workplace and beyond. Batchelor argues that traditional leadership models, often characterized by command-and-control styles, are no longer effective in today's rapidly changing work environments.

Read moreBOB BATCHELOR LAUNCHES NEW PUBLISHING VENTURE: TUDOR CITY BOOKS

International bestselling author Bob Batchelor, renowned for his expertise in cultural history and biography, has launched Tudor City Books, a new publishing company headquartered in Raleigh, North Carolina. Specializing in a range of subjects, including crime fiction, entertainment and pop culture history, memoir, and biography, Tudor City Books aims to bring exceptional works to a broader audience.

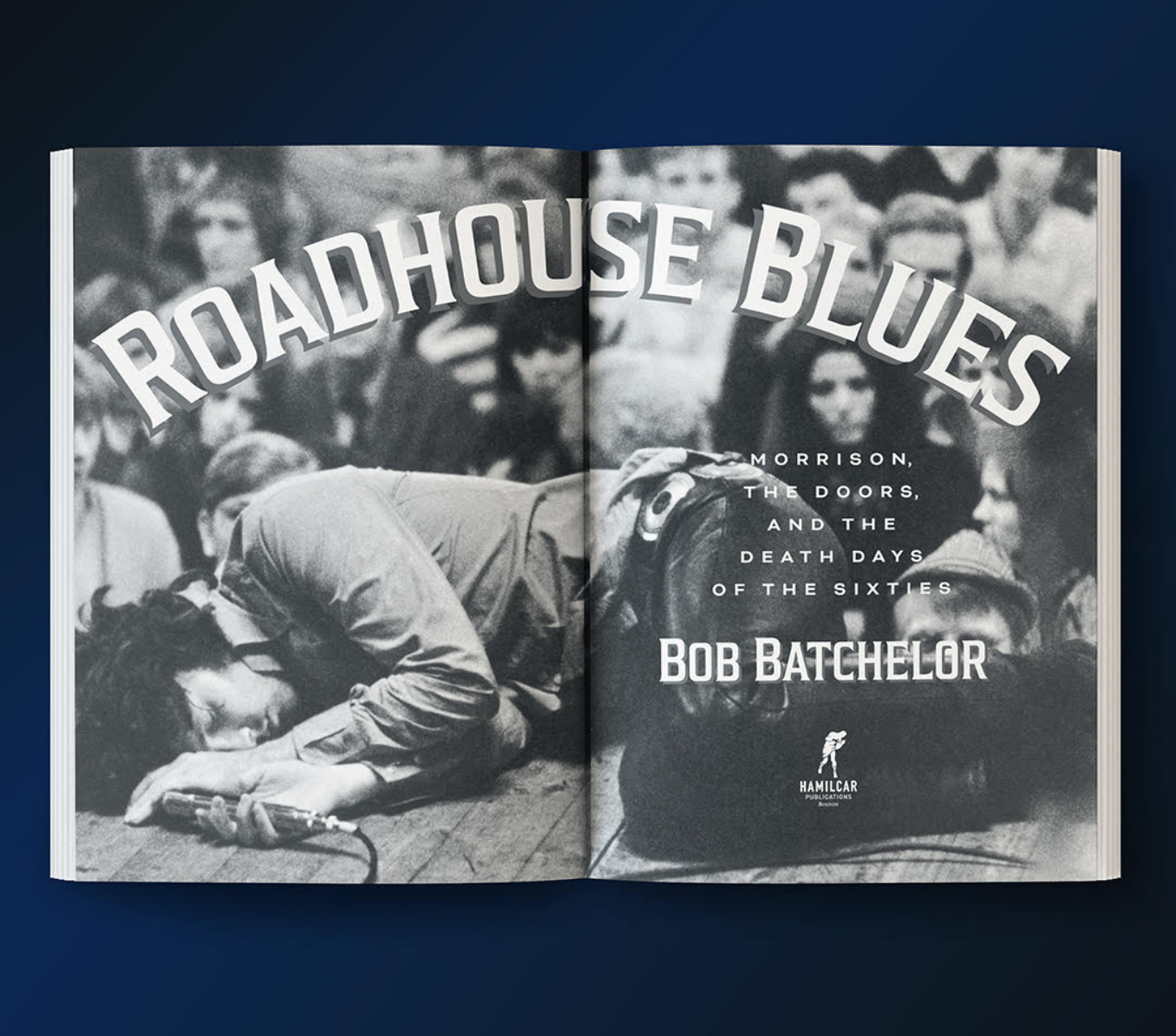

Read moreROADHOUSE BLUES: MORRISON AND THE DOORS LIKE YOU'VE NEVER SEEN BEFORE!

Reviews of ROADHOUSE BLUES

Roadhouse Blues: Morrison, the Doors, and the Death Days of the Sixties won the 2023 IPA Book Award in Music and has been lauded by critics, readers, and Doors aficionados across the globe.

2023 Independent Press Award for Roadhouse Blues

REVIEWS

“Fascinating, informative, extraordinary, and essential reading for the legions of Jim Morrison fans.” – Midwest Book Review

“Bob Batchelor writes with great eloquence and insight about the Doors, the greatest hard-rock band we have ever had, and through this book, we plunge deeply into the mystery that surrounds Jim Morrison. It is Batchelor’s warmth and compassion that ignites Roadhouse Blues and helps explain Morrison’s own miraculous dark fire.” – Jerome Charyn, PEN/Faulkner Award finalist

Splash page for Roadhouse Blues, designed by the eminent Brad Norr

“The most important book for Doors fandom since No One Here Gets Out Alive—and incomparably better! Grouped with Ray, Robby, and John’s books, this is the fourth gospel for fans of The Doors.” – Bradley Netherton, The Doors World Series of Trivia Champion and host of the “Opening The Doors” podcast

“Batchelor writes well and his narrative flows smoothly. His work is an insightful look at the Doors as creative artists and a compelling portrait of Morrison.” – Thomas Hauser, Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award nominee

“Smart, engaging…Batchelor has a technique and perspective that runs through his work: paint a vivid description of what happened, but then, more than a mere journalist or biographer, delve into how it happened and then why it happened. The what is documentarian; the how, and especially the why, require the kind of analysis with imagination that Roadhouse Blues provides.” – Jesse Kavadlo, PopMatters

Roadhouse Blues, published by Hamilcar Publications

JIM MORRISON'S LAST ALBUM, L.A. WOMAN RELEASED 53 YEARS AGO TODAY!

Blues- and Jazz-Infused Music From America’s Greatest Rock Band; Excerpt from Roadhouse Blues

The Doors released L.A. Woman on April 19, 1971, and Jim Morrison would be dead about 10 weeks later. The last album during his lifetime solidified the band’s standing and the singer’s legacy as an iconic figure in rock ‘n roll history.

Roadhouse Blues author Bob Batchelor with L.A. Woman

EXCERPT FROM ROADHOUSE BLUES: MORRISON, THE DOORS, AND THE DEATH DAYS OF THE SIXTIES (HAMILCAR PUBLICATIONS)

While incarceration loomed, Jim and the band got back into the studio. Ray, Robby, and John understood the seriousness of the situation. Densmore claimed that saving Jim was the band’s first priority: “Fuck, man, if we don’t get an album or two more out of Jim, so what? Maybe we’ll save his life.” They thought the creative process would reverse the spiral. The strategy had worked with Morrison Hotel.

Ironically, the album that would later be named after their adopted home—L.A. Woman—would be made without longtime producer Paul Rothchild. He hated the songs the band planned to use for the new record, telling them, “It sucks…it’s the first time I’ve ever been bored in a recording studio in my life.” At a dinner, according to Hopkins and Sugerman, Rothchild told them that they should produce themselves with Botnick’s assistance.

Although Rothchild may have disliked the tracks and sound, some felt that he still mourned Janis and was afraid to watch Jim’s journey down a similar path toward destruction. He also wanted a more controlled sound and believed the band couldn’t deliver, based on Jim’s commitment to partying and the tension that it caused with Ray, Robby, and John.

Rothchild had a point. Krieger remembered Jim’s drinking, saying, “When he got too drunk, he would become kind of an ass. It got harder and harder to be close with him.” The band kind of lined up on one side— on the other, Jim and his increasing number of drinking buddies and hangers-on. In his memoir, Ray called them “reprobates…slimeballs, and general Hollywood trash.”

Still, Botnick agreed to co-produce the next album, and the band went to work to perfect the demos and create several more. They set up shop at the Doors offices at 8512 Santa Monica Boulevard, which felt safe and secure for the band. With Jim across the street at the fleabag Alta Cienega Hotel, Robby remembered that the singer was reenergized by the process. Like the previous album, Botnick wanted to get a live feel. He said, “Go back to our early roots and try to get everything live in the studio with as few overdubs as possible.”

The Doors perform at the Hollywood Bowl

Continuing the creative process that had worked on Morrison Hotel, the band wrote songs together, often from poems Jim had been working on over the years. Adding to the new vibe, they used Elvis’s bassist Jerry Scheff and rhythm guitarist Marc Benno to add a deeper, more lush tone. Morrison sang in the adjoining bathroom to get the sound he wanted. To capture the desired live spirit, they didn’t do many takes and kept overdubs to a minimum.

Morrison’s concept of L.A. Woman centered on imagining the city as a sexy woman, his way to pay homage to the “City of Lights.” They also continued to explore what it meant to live on the West Coast and in the contemporary world. The sound was expansive, more alive than what they had done recently, despite the weight of Jim’s conviction.

The title track “L.A. Woman,” according to Densmore, epitomized the new sound, particularly Jim’s anagram for his name. “‘Mr. Mojo Risin’ is a sexual term,” the drummer explained. “I suggested that we slowly speed the track back up, kind of like an orgasm.” For Robby, it was the teamwork that pulled the best work from the band. “The title track was distilled from jam sessions, with all of us contributing equally,” he remembered. “Jim started with a handful of lines and added lyrics as he went while John kept it interesting with time changes and Ray and I harmonized on the melody and traded solos.”

In 2022, the editors at Bass Player named the bassline of “L.A. Woman” one of the forty greatest of all time. “True to the production values of the day, Ray Manzarek’s throbbing keyboard bass is all low frequencies and no mids, adding to its thunderous presence,” they said. That unforgettable sound “takes everything that was best about The Doors—acid-drenched psychedelia, a threatening blues edge and that era-defining drone—and anchors it all with a rock-solid bassline.” The enduring success of the song and its ranking among the best ever recorded is a demonstration of what the Doors could still create, particularly in their stripped-down, blues-infused era.

Despite the stress Jim experienced while putting the album together, the power of his vocals propelled the record. Morrison sounded lively—perhaps even sober—between takes. “I don’t follow orders. I’m just a dumb singer,” he playfully told his bandmates during one interval. Yet under Botnick’s guiding hand, songs like “L.A. Woman” came together, as the producer explained, with “a little bit of woodshedding.”

According to Robby, much of the beauty of “L.A. Woman” came from how he worked with Jim to bring the vocals and guitar into sync. “During the verses, I do these little answer lines to Jim’s vocals. That was just a natural thing he and I would do. He’d sing something and I’d respond.” The improvisation gave the song a timeless vibe, ramping up the power of the live feel. If you close your eyes, you can feel the sun on your face and hear the motor roaring as you’re chugging down the Pacific Coast Highway. The glint off the ocean is blinding, but the air is clean, and the grit of the city is in the rearview mirror.

As a tribute to the great jazz pianist and composer Duke Ellington, Krieger wrote “Love Her Madly,” whose title comes from the way the Duke ended his shows by telling audiences: “We love you madly!” It took the rest of the band, however, to work it into the Doors groove. “We workshopped it together,” the guitarist said.

Roadhouse Blues by cultural historian and biographer Bob Batchelor

For the band, working collectively always worked best. “We tickled them and cajoled them and pampered them, and whipped them into line,” Ray said of those tracks. “It was like the old days.” L.A. Woman was a testament to that collaborative spirit.

WHAT DID STAN LEE DO DURING WORLD WAR II

A Fact-Filled, Frequently Asked Question by Stan Fans Everywhere!

Pearl Harbor brought the war to America. Winning hinged on creating an interlocked infrastructure to support the troops. Businesses of all sizes rallied to the cause. Democracy hung in the balance!

Although still a teenager, Stan Lee enlisted on November 9, 1942, just as the US faced its first skirmish on the coast of North Africa. He took the Army General Classification Test and scored high, qualifying for the Signal Corps.

The war was good for comic books. In 1943 more than 140 were on newsstands, reportedly “read by over fifty million people each month.” In 1944, Fawcett’s Captain Marvel Adventures sold 14 million copies (up 21 percent). Superhero titles drove sales, but publishers also expanded into humor, funny animals, and teen romance. Captain America remained Timely’s most popular series.

“How would you like my job?” Lee asked his friend Vince Fago.

Veteran animator Fago had worked on Superman and Popeye for Fleischer Studios. Battling with Disney, Max Fleischer’s shop differed by focusing on human characters, such as Betty Boop and Koko the Clown, rather than talking mice, ducks, and other anthropomorphic figures. Martin Goodman paid Fago $250 a week.

The fighting overseas was heavy stuff; readers yearned for lighter comedic fare. Fago specialized in funny animals, so Timely used Disney as a model, essentially transforming into Disney-lite. They published amusing animal tales, such as Comedy Comics and Joker Comics. Lee had concocted some of these characters, like Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal (co-created with artist Al Jaffee, the future Mad magazine illustrator). Fago estimated that each comic had a print run of about 500,000. “Sometimes we’d put out five books a week or more,” Fago remembered. “You’d see the numbers come back and could tell that Goodman was a millionaire.”

Goodman also wanted to gain female readers. Miss America, a teenage heiress who gained superhuman strength and the ability to fly after being struck by lightning, first appeared in Marvel Mystery Comics #49 (November 1943), with Human Torch and Toro on the cover thwarting a Japanese battleship. In January 1944, Miss America became a title character. However, when sales dropped, the next issue was delayed until November, publishing as Miss America Magazine #2. A real-life model portrayed the character in her superhero outfit. For the relaunch, Fago and his team gradually eliminated superhero material in favor of topics deemed more appropriate for teen girls.

***

Lee went through basic training at Fort Monmouth, an enormous base in New Jersey that housed the Signal Corps. It also served as a research center – radar was developed there and the handheld walkie-talkie. In subsequent years, they would learn to bounce radio waves off the moon.

Stan Lee with his beat-up jalopy

Stan learned how to string and repair communications lines – a path to combat duty (like his former boss Jack Kirby). Army strategists knew wars were often won by infrastructure – the Signal Corps kept communications flowing, but they could barely keep up with demand. Other training centers opened at Camp Crowder, Missouri, and Camp Kohler, near Sacramento. By mid-1943, the Corps’ consisted of 27,000 officers and 287,000 enlisted men, backed by another 50,000 civilians.

Pearl Harbor heightened concern that German subs or planes might mount a surprise attack during the cold New Jersey winter. Lee patrolled the base perimeter, claiming the frigid wind whipping off the Atlantic nearly froze him to death.

The beachfront burden ended when Lee’s superior officers discovered his work in publishing. They placed him in a special outfit producing instructional films and other wartime materials. Lee wrote fast and in a breezy style that recruits and trainees could comprehend.

The Army liked these traits too. At the Training Film Division, based in Astoria, Queens, he joined eight other artists, filmmakers, and writers to create public relations pieces, propaganda materials, and information-sharing documents. Education was critical for the war effort. Imagine, millions of young Americans were enlisting and they collectively had about an eighth grade education. They needed to learn how to fire machine guns, run offices, and build bridges, barracks, and other essentials necessary to win the war. They needed training materials that they could understand and put to immediate use.

The Army purchased a large building flanked by rows of tall, narrow windows at 35th Avenue and 35th Street. Colonel Melvin E. Gillette commanded the efforts. Inside the Army built the largest soundstage on the East Coast, enabling filmmakers to create a variety of military settings and scenes. The old movie studio (built in 1919) soon rivaled the major Hollywood production companies.

Prop department at the Long Island facility

“I wrote training films, I wrote film scripts, I did posters, I wrote instructional manuals,” Lee said. “I was one of the great teachers of our time!” The Signal Corps group included many famous or soon-to-be-famous individuals, including three-time Academy-award winning director Frank Capra, New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams, and children’s book writer and illustrator Theodor Geisel, who the world already knew as “Dr. Seuss.” The stories that must have floated around during staff meetings!

Lee took up a desk in the scriptwriter bullpen, to the right of eminent author William Saroyan – at least when the pacifist author visited the office. Saroyan, who had won a Pulitzer Prize (but rejected it) for his play The Time of Your Life (1939), usually worked from a Manhattan hotel. Lee and the others, including screenwriter Ivan Goff and producer Hunt Stromberg Jr., earned the official Army military occupation specialty designation: “playwright.”

As home front efforts intensified, Lee traveled to other bases, essentially crisscrossing the Southeast and Midwest. Each base had a critical need for easy-to-understand manuals, films, and public relations documents. Stan wrote about using combat cameras, caring for weapons, and other topics he knew little about. In these situations, he utilized a familiar motto – simplify the information. “I often wrote entire training manuals in the form of comic books. It was an excellent way of educating and communicating.”

One post took Lee to Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indiana, just northeast of Indianapolis – a jarring locale for a New York City native who had not ventured outside the city. He worked with the Army Finance Department, which struggled to keep up with payrolls. Watching the wannabee-accountants march, Lee noticed they lacked vigor. He penned a song for them, inserting new lyrics over the famous “Air Force Song.” The peppy tune included memorable lines, like “We write, compute, sit tight, don’t shoot,” but it improved morale.

Stan used humor to help the men absorb the complex procedures. “I rewrote dull army payroll manuals to make them simpler,” Lee remembered. “I established a character called Fiscal Freddy who was trying to get paid. I made a game out of it. I had a few little gags. We were able to shorten the training period of payroll officers by more than 50 percent.” He joked: “I think I won the war single-handedly.”

“I rewrote dull army payroll manuals to make them simpler. I established a character called Fiscal Freddy who was trying to get paid. I made a game out of it. I had a few little gags. We were able to shorten the training period of payroll officers by more than 50 percent...I think I won the war single-handedly.”

Lee moved to another project, calling it “my all-time strangest assignment,” creating anti-venereal disease posters aimed at troops in Europe. Sexually transmitted diseases had plagued armies throughout history. American leaders considered the effort deadly serious. Despite implementing extensive education campaigns, the military still lost men to syphilis and gonorrhea. The British – less willing to confront the taboo epidemic – had 40,000 men a month being treated for VD during the Italian campaign.

Military leaders went to extreme measures to thwart STDs, including the creation of propaganda posters showing Hitler, Mussolini, and Tojo deliberately plotting to disable Allied troops via disease. Many of these images, such as the ones famously created by artist Arthur Szyk, depicted the Axis leaders as subhuman animals, with rat-like features or as ugly buffoons.

Unsure how to combat the scourge, Lee promoted the prophylactic stations set up by the armed forces. Men visited the huts when they thought they were infected, which involved a series of rough and painful treatments. “Those little pro stations dotted the landscape,” Stan said, “with small green lights above the entrance to make them easily recognizable.” He wrestled with different taglines, ultimately hitting upon the simplest: “VD? Not me!”

Lee illustrated the poster with a cartoon image of a happy serviceman walking into the station, the green light clearly visible. Army leaders liked its simplicity and flooded bases with the posters. Ironically, the print may have ranked among Lee’s most-seen, yet also the most roundly ignored.

According to lore, the other “playwrights” couldn’t keep up with Stan, forcing the commanding officer to order him to slow down. While it is difficult to quantify the importance of the films, posters, photos, and training aids the Signal Corps produced, analysts determined they cut training time by 30 percent. Signal Corps efforts also provided from 30 percent to 50 percent of newsreel footage for movie theaters, which kept the public informed. Lee, Capra, Geisel, and the other Army “playwrights” did vital work.

Lee used downtime to keep his fingers dipped in Timely ink and his pockets filled with Goodman’s money as a freelance writer. With the extra money, Stan purchased his first automobile for $20 – a 1936 Plymouth with a fold-up windshield. Stationed near Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, the unique windshield allowed the warm Southern air to blow in his face as he cruised the back roads of tobacco country.

No matter where the Army sent him, Lee received letters outlining stories from Fago every Friday. Stan then typed up the scripts, sending them back on Monday. In addition to working on comics, Lee also helped out with the pulps. He wrote cartoon captions for Read! magazine, including this short ditty in January 1943: “A buzz-saw can cut you in two / A machinegun can drill you right thru / But these things are tame, compared— / To what a woman can do!” The accompanying drawing shows a plump woman feeding her bald husband – chained to a doghouse. The ribald humor fit within Goodman’s magazines, filled with sexist overtones and racy photographs.

Stan also wrote mystery-with-a-twist-ending short stories, similar to the ones in Captain America. In “Only the Blind Can See” (Joker, 1943-1944), the gag is on the reader, who eventually realizes a supposedly blind panhandler (assumed a phony) was telling the truth. Written in second person so Lee can speak directly to the reader (addressed as “Buddy”), one learns that the down-on-his-luck beggar had been too prideful. The truth comes to light when a speeding car hits the blind man. These short stories served as training for the science fiction and monster comic books that Lee would write after the war.

Stan’s afterhours writing for Timely went largely unnoticed by his superiors, but once got him arrested (in typical Lee madcap fashion). One Friday a bored mail clerk overlooked Stan’s letter, reporting an empty mailbox. Lee swung by the closed mailroom on Saturday and spied a letter in his cubby – with the Timely return address.

Fearful of missing a deadline, Lee asked the officer in charge for the letter. The harried officer told Lee to worry about the mail on Monday. Angry, Stan used a screwdriver to gently loosen the hinges and freeing the missive. When he realized what Lee did, the mailroom supervisor went berserk, reporting him to the base captain. They charged Lee with mail tampering and threatened to throw him in Leavenworth prison. Luckily, the colonel in charge of the Finance Department intervened. In this instance, Fiscal Freddy really did save the day!

***

Stan’s signature and a quick roll of his ink-stained thumb across the Army discharge papers made it official – in late September 1945 Sergeant Lee returned to civilian life. Practically before the ink dried, the 23-year old roared off base. His new black Buick convertible had hot red leather seats, flashy whitewall tires, and shiny hubcaps – a noticeable upgrade from the battered, $20 Plymouth.

Lee received a $200 bonus (called “muster out pay”), given to soldiers so they could jumpstart their post-military lives. Half went into a savings account and Lee pocketed the rest. The Army had allotted him $42.12 to get back to New York City from Camp Atterbury in central Indiana, about 50 miles south Fort Harrison.

Excited to get back to the Big Apple, Stan joked that he “burned my uniform, hopped into my car, and made it non-stop back to New York in possibly the same speed as the Concorde!” The editor desk awaited in the new headquarters on the fourteenth floor of the Empire State Building. Lee zoomed off on the 700-mile trip to the Big Apple.

Stan Lee: A Life by biographer and cultural historian Bob Batchelor

FLASH SALE -- MAD MEN: A CULTURAL HISTORY, $2.99

Get the eBook at Deep Discount! Limited Time…

"Valuable insight into the historical moments of the 1960s that inform and shape our understanding of the television series." -- Journal of American Culture

Mad Men: A Cultural History

Mad Men: A Cultural History -- FLASH SALE -- $2.99

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

NEW BOOK DEAL -- NOLAN RYAN BIOGRAPHY

BOOK DEAL ANNOUNCEMENT

Cultural historian and biographer, author of Stan Lee: A Life and The Bourbon King: The Life and Crimes of George Remus, Prohibition's Evil Genius Bob Batchelor's THE RYAN EXPRESS: NOLAN RYAN'S JOURNEY TO BASEBALL IMMORTALITY. Deep dive into the extraordinary life and times of Nolan Ryan, the iconic Hall of Fame pitcher and strikeout king. This meticulously researched and entertaining written biography explores the remarkable career of the pitcher whose name is synonymous with the fastball. His blazing speed enabled him to strike out more batters than any player ever, a record that will never be eclipsed, just as his seven no-hitters will live on in immortality, to Christen Karniski at Rowman & Littlefield, in a nice deal, in an exclusive submission, for publication in summer 2026.

UNMASKING STAN LEE: FROM SUPERHEROES TO CULTURE IN 10 PIVOTAL MOMENTS -- GREAT LIVES LECTURE SERIES AT UNIVERSITY OF MARY WASHINGTON

“Stan Lee: Spider-Man and Marvel Comics” — February 22, 2024

The Yuh Prosthodontics Lecture

William B. Crawley Great Lives Lecture Series

Biographical Approaches to History and Culture begins its third decade with a program on January 16, 2024. The schedule includes a total of 18 programs, running through March 28.

Bob Batchelor lecture on Stan Lee at University of Mary Washington

Join cultural historian Bob Batchelor on an exhilarating journey into the extraordinary life of Stan Lee, an icon whose legacy is as epic as the superheroes he co-created. Renowned for film cameos as the Marvel movie franchise conquered the world, Lee would have been 101 today, providing the perfect moment to delve into his profound impact on contemporary America and global culture.

Batchelor presents Lee’s life in 10 pivotal moments, each encapsulating an era of modern history. From the Roaring Twenties to the Great Depression, the American Century to the twenty-first century, his journey mirrors the sweeping narrative of the nation itself. Lee’s vision and creative genius revolutionized pop culture, introducing us to superheroes that were as complex and fallible as their creator (and all of us).

Experience the highs and lows, drama and humor of Lee’s life via a narrative that not only explores a cultural visionary, but also uncovers the heart of a man who dreamed of writing the Great American Novel and, in the process, rewrote the script of global pop culture. This is the story of Stan Lee, a true American icon, whose legacy continues to entertain and inspire generations around the world. Excelsior!

BRIEF BIO

A 3-time winner of the Independent Press Book Award, cultural historian Bob Batchelor has been hailed as “one of the greatest non-fiction writers and storytellers” by New York Times bestselling biographer Brian Jay Jones. His books examine modern popular culture icons, events, and topics, from comic books and music to literary figures and history’s outlaws.

By day, Bob is a diversity, equity, and inclusion advocate and ally at The Diversity Movement, a Raleigh DEI consultancy. By night, he is the author of 14 books, editor of 19 books, and has been published in a dozen languages. He is best known as biographer of Marvel icon Stan Lee, having written 3 books on him and numerous essays and chapters, one on Spider-Man appearing in Time.

An interdisciplinary writer, Bob has published books on Jim Morrison and the Doors, Bob Dylan, The Great Gatsby, Mad Men, and John Updike, among others. He wrote an award-winning illustrated history of Rookwood Pottery, the revolutionary company that became one of the great art potteries in the world, and The Bourbon King: The Life and Crimes of George Remus, Prohibition’s Evil Genius, a rollicking tale of the infamous bootleg baron, as widely known in the Roaring Twenties as Warren G. Harding and Babe Ruth.

Bob’s work has appeared or been featured in the New York Times, Cincinnati Enquirer, Los Angeles Times, and PopMatters. He created the podcast “John Updike: American Writer, American Life” and “Tales of the Bourbon King: The Life and True Crimes of George Remus.” He has appeared as an on-air commentator for The National Geographic Channel, PBS NewsHour, PBS, the BBC, and NPR. Bob hosted “TriState True Crime” on WCPO’s Cincy Lifestyle television show.

Bob earned his doctorate in American Literature from the University of South Florida and an M.A. in History from Kent State University after graduating from the University of Pittsburgh. He has taught at universities in Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, as well as Vienna, Austria. Bob and his wife, antiques and vintage expert Suzette Percival live in North Carolina and have two wonderful teenage daughters.