The Doors Experience the “Human Be-In” and Go Gaga for Beat Poets and Hippie Culture

As 1967 began, “Jim Morrison” was a guy on your bowling team if you lived in Charleston, West Virginia, or one of the many local realtors hustling for business in Sandusky, Ohio. There were plenty of men all across the country named “Jim Morrison,” but none of them was a rock star.

The name itself had yet to enter the national consciousness. The world had yet to meet the future Lizard King.

The Swiss American Hotel in San Francisco’s Chinatown District, where the Doors stayed on their first tour in January 1967

After their self-titled first album was released on January 4, 1967, the Doors remained little more than a really popular local Los Angeles band. In contrast to today’s blockbuster mentality in which all the marketing and publicity efforts focus on the release date and immediate success, the debut record progressed steadily on the charts. For four young men hungry for success, a new album meant playing wherever they could play and being seen wherever they could be seen.

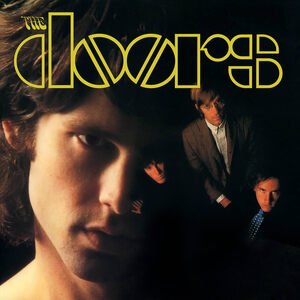

The Doors self-titled debut album

Whether looking at album sales, considering concert tickets sold, or listening to the radio, it would be impossible to separate the youth-oriented marketplace from its musical soundtrack. The Baby Boom generation had more disposable income than any generation in American history. They used a significant portion of the money to place music at the center of their lives. The celebrity industry responded in kind, unleashing an army of publicists, advertisers, and marketers hoping to turn a new band into the next Beatles.

The Elektra promotional team had a challenge with the Doors. The band didn’t look or sound like anything else in the market, which is always a problem because then potential audiences can’t place the hot new thing. Awareness was key—they had to get people to sample the Doors.

The Doors didn’t fit into conventional boxes, even for a rock band in 1967

Promotion had begun before the album’s release when the band made their first live TV appearance on a show called Shebang that ran on the hometown station KTLA on Sunday nights. Hosted by Casey Kasem and produced by Dick Clark, the show featured teenagers dancing to popular acts, similar to American Bandstand, which had launched in the Fifties. Local versions like Shebang were becoming more popular as more teens meant more bands. Although a live appearance, the Doors lip-synched “Break On Through,” the album’s first single.

The band was already known locally for their psychedelic sound and Jim’s wild stage antics, but the Doors looked tame on Shebang. The stage setup was a colorful mix of Day-Glo yellows, reds, and oranges, mixed in with a bunch of houseplants. According to the other bandmembers, Morrison barely attempted to lip-synch, but it wasn’t out of arrogance. “We were clearly nervous,” John said. “I mean, Jim won’t even look at the camera or anything.” The singer was a long way from becoming the Lizard King.

A year later the Doors would be the hottest band in America…and maybe the world.

The Doors on the Los Angeles music-dance show, Shebang, lip-synching “Break On Through”

With the first album in stores, the Doors toured to support the release. California was the focus, naturally, but they immediately went to San Francisco, which was dicey for any LA band. At different ends of the state, the two cities shared little in terms of style and culture and many music insiders believed a band couldn’t be popular in both places.

The initial shows were good, but the Doors opened for more popular bands like the Young Rascals and the Grateful Dead. In their off-hours, the band soaked up San Francisco’s culture. They stayed at the Swiss American Hotel, in the heart of the city’s Chinatown District, a colorful neighborhood filled with wonderful restaurants and shops. They ate burgers across the street from the hotel at Mike’s Pool Hall, a local hang that had been made famous by artists, poets, and others looking for fun. Lawrence Ferlinghetti—who Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek idolized—made Mike’s Place famous in the poem “Autobiography” from his collection A Coney Island of the Mind (1958).

Mike’s Pool Hall in San Francisco—Immortalized in Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s poem “Autobiography”

Part of the band’s education in the City by the Bay took place at The Human Be-In, a festival featuring music, activists, and spirituality in Golden Gate Park. Twenty thousand people had gathered to protest a California law banning LSD that had passed the previous fall. The Doors played elsewhere throughout the weekend but weren’t established enough to play the festival.

Alongside famous poets like Allen Ginsberg and Michael McClure, activist and educator Timothy Leary called for the crowd to “Turn on, tune in, drop out,” a phrase that would become legendary and epitomize the psychedelic era. Leary’s mantra and the large crowds that filled the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood caught the national media’s attention, which brought the hippie movement into the homes of millions of Americans via news reports and TV segments.

It’s impossible to gauge the impact the Doors had on listeners in San Francisco, but their sound was certainly alien to the trippy vibe local fans loved. Plus, San Francisco musicians were quick to judge (negatively) the energy and music coming out of Southern California.

On the surface, Ray, Robby, Jim, and John seemed to fit in as openers for the Dead, but Jerry Garcia disliked Morrison almost immediately. According to writer Dennis McNally, “Morrison struck him as the embodiment of Los Angeles…the triumph of style without substance. The Doors had no bassist and consequently sounded thin to him, and Morrison’s imitation of Mick Jagger did not impress him.”

In 2007, Manzarek recalled the event fondly, as well as the impact it had on the group:

“We get to Golden Gate Park and there are 30,000 hippies, a sight unlike any that we have ever seen, colorful dress, long hair, jewels, dancing…The feeling was so free and spiritual and loving. It was like the beginning of the change. A new generation had been born that day, conceived in liberty, peace and love. And we thought, this is it, we are going to change the world.”

A newspaper photo of the large crowds at the Human Be-In in San Francisco—”Hippy Haven”

For more on the Doors, the Sixties, and the era, pick up a copy of Bob Batchelor’s Roadhouse Blues: Morrison, the Doors, and the Death Days of the Sixties, also available in audiobook.

Roadhouse Blues by cultural historian Bob Batchelor