BOOK DEAL ANNOUNCEMENT

Cultural historian and biographer, author of Stan Lee: A Life and The Bourbon King: The Life and Crimes of George Remus, Prohibition's Evil Genius Bob Batchelor's THE RYAN EXPRESS: NOLAN RYAN'S JOURNEY TO BASEBALL IMMORTALITY. Deep dive into the extraordinary life and times of Nolan Ryan, the iconic Hall of Fame pitcher and strikeout king. This meticulously researched and entertaining written biography explores the remarkable career of the pitcher whose name is synonymous with the fastball. His blazing speed enabled him to strike out more batters than any player ever, a record that will never be eclipsed, just as his seven no-hitters will live on in immortality, to Christen Karniski at Rowman & Littlefield, in a nice deal, in an exclusive submission, for publication in summer 2026.

ANNIVERSARY OF JIM MORRION'S MYSTERIOUS DEATH IN PARIS

Jim Morrison Died on July 3, 1971 — 52 Years Later, We are Still Contemplating His Iconic Life

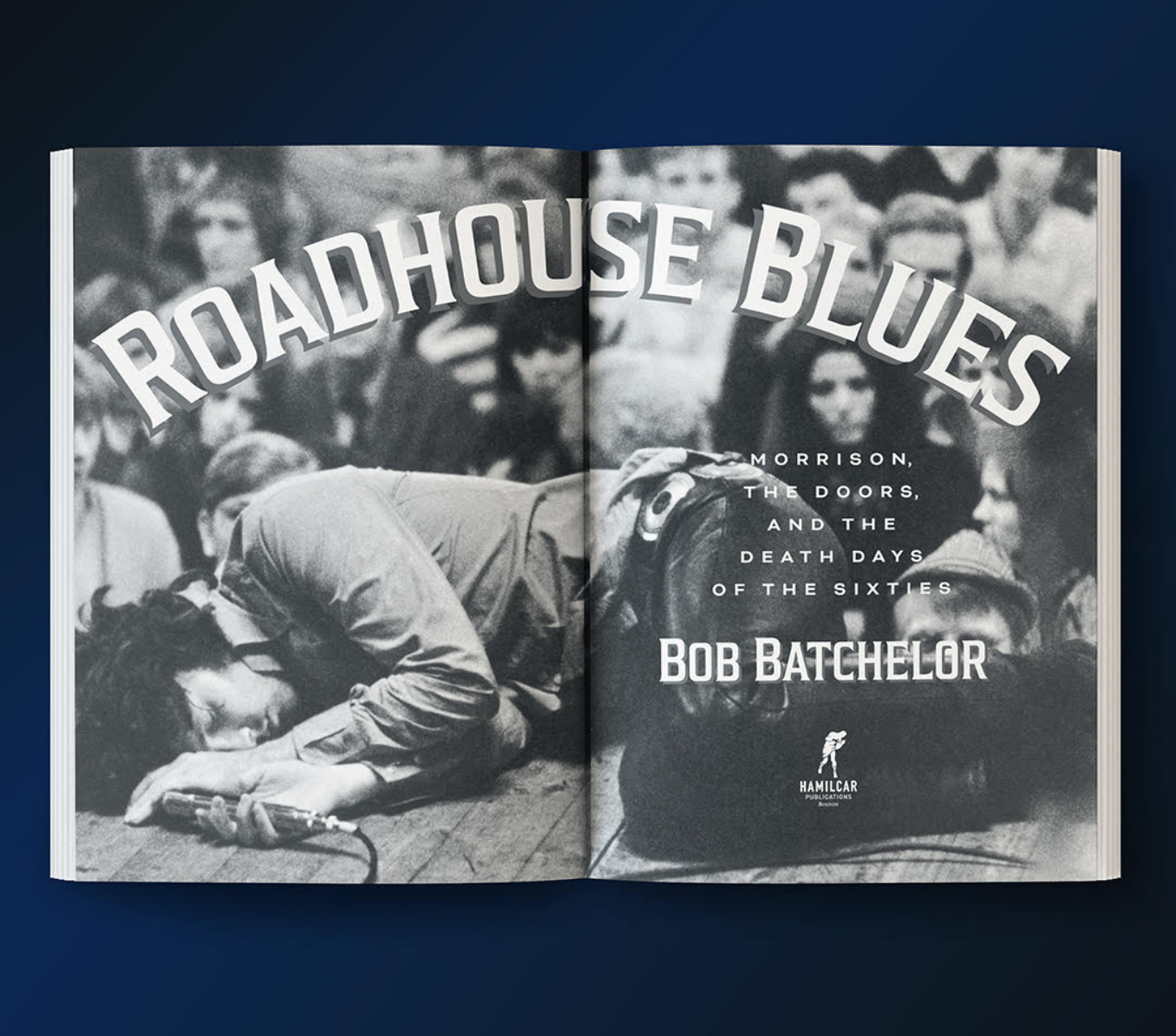

Roadhouse Blues by cultural historian Bob Batchelor, published by Hamilcar Publications

Below is an excerpt from Roadhouse Blues: Morrison, the Doors, and the Death Days of the Sixties that looks at Jim Morrison in the Twenty-First Century.

Jim Morrison in a thoughtful moment during the Isle of Wright concert

Jim Morrison in the Twenty-First Century

What can a singer dead for more than five decades tell us about twenty-first-century America? Well, if we’re searching for insight from the life and enduring legend of Jim Morrison, the answer is contained in an unending string of impulses that combine to create the contemporary world.

Morrison matters today because we can use his brief life and long afterlife to examine the issues and topics that still bedevil modern society. From women’s rights to our thinking about war and freedom, Morrison’s vantage offers context. He also helps us understand philosophical questions about history, nostalgia, fame, and celebrity as an industry.

Looking at Morrison’s life has another critical component—it demonstrates how our thinking transforms over time. The most straightforward example is how he was venerated in the 1980s by a generation who viewed him as the ultimate party animal. Following his lead, Gen Xers and others could give the middle finger to people in roles of authority while reveling in his booze-filled, hedonistic lifestyle.

While this perspective may always be a part of Morrison’s legacy based on how young people choose to exert their freedoms, examining his life from today’s viewpoint reveals a young man struggling with addiction and desperately in need of help. From Jim’s life, we can learn much about addiction, recovery, and treatment in hopes of saving lives.

While generations of observers have filled Morrison with any number of meanings, near the end of his own life, he realized that he was on a search for something more. Even though many people would have traded their lifestyles for his in an instant, he hoped for a deeper purpose:

I’m not denying that I’ve had a good time these last three or four years…met a lot of interesting people and seen a lot of things in a short space of time…I can’t say that I regret it, but if I had it to do over again, I would have gone more for the quiet, undemonstrative little artist plodding away in his own garden trip.

***

Perhaps the greatest debut album of all-time!

“I see myself as a huge fiery comet, a shooting star. Everyone stops, points up and gasps ‘Oh, look at that!’ Then whoosh, and I’m gone…and they’ll never see anything like it ever again…and they won’t be able to forget me—ever.”

—Jim Morrison

***

What we do not get from Morrison—as a person with a full range of human complexities—is a single perspective or fixed point on how to interpret him or his era. He is part of a larger puzzle for understanding the Sixties and early Seventies. What I argue, along with other historians, is that history is the craft of presenting information based on viewpoints, analysis, documentation, and other points of reference, but not what actually happened. Even if you were beside Jim as he lived his life, it would not be history but rather your interpretation of that time frame from your own perspective. Historians create the framework.

This is important in examining and piecing together a contentious era like the Sixties. We are attempting to shine light into the dark night that brings together the lived experiences and lifetimes of people who valued the time for different reasons. For example, I contend that it is impossible to comprehend the Sixties without layering in Vietnam, whether economic, political, or cultural. However, I’ve interviewed people who have never mentioned the war or its consequences on their lives. It is not as if these individuals lived in an alternate reality; it’s just that they found a way to circumvent the topic in a way that makes sense to them in their recollections.

Even when examining the parts of the Sixties that seemed to flow logically into the next, for example, as if the self-help and meditation of the 1970s had to be the outcome of the free-love and activist 1960s, we understand this equation is never the straight line it might appear to be on paper, film, or video. In fact, when it does seem like a direct path, it’s most likely that someone has created that narrative.

For literary critic Morris Dickstein, who grew up in the 1960s, a multitude of influences melded to create the era’s foundation: “The cold war, the bomb, the draft, and the Vietnam War gave young people a premature look at the dark side of our national life, at the same time that it galvanized many older people already jaded in their pessimism.” The role the Doors played in exposing the dark side and bringing it to the mainstream is significant.

The depth of Morrison’s life called for writing this book. Few cultural icons have had a more lasting impact. But, as I have shown, the importance of the Doors includes the group too. It wasn’t strictly the Jim Morrison show, although his myth is of course a big factor in the band’s enduring fame.

This book is a reassessment of a significant era in American history and an example of how we might gain from that exercise. According to David Strutton and David G. Taylor: “The examination of history allows one to acquire experience by proxy; that is, learning from the harsh or redemptive experiences of others…Mythology is less reliable than history as narrative of actual experience; yet it may hold more power than history.”

By revisiting Morrison, the Doors, and the death days of the Sixties, we give the era meaning as it existed in its day and at the same time create a tool to use to navigate our lives and the future. For example, Vietnam has become synonymous with America’s intervention in overseas wars, particularly against enemies that appear doomed on paper. The wars in the Middle East over the last several decades have been examined via the Vietnam lens, but the comparison sadly did not lead to a different outcome. In this case—and concerning future warfare—we might ask ourselves the reasonable question: Where were the protesters who played such a pivotal role in illuminating what was happening in Southeast Asia in the Sixties and Seventies? For that matter, why were the journalists in the Middle East “embedded” rather than emboldened like their media forbearers? Perhaps the most significant difference was the draft, but the real emphasis is that reevaluating the decades gives a measure of what is happening today—and offers a potential lens for anticipating the future.

***

We all need tools to examine society’s larger questions, but Morrison’s life can also help us understand each other on a more intimate level. How did Jim view himself in the world?

One of the most striking aspects of Jim’s life versus the legend that grew after he died is the gap between what people thought of the public person versus the more private individual. After his death, the mythmaking and apocryphal aspects of his life seemed to eclipse who he really was.

For example, journalist Michael Cuscuna said, “The antithesis of his extroverted stage personality, the private Morrison speaks slowly and quietly with little evident emotion, reflectively collecting his thoughts before he talks. No ego, no pretensions.” For writer Dylan Jones, Jim stood as “the first rock’n’roll method actor” and “an intellectual in a snakeskin suit.” Ultimately, hinting at the singer’s true nature, he saw “a man who, when he revealed himself, was often to be found simply acting out his own fantasies.”

Jim embraced this notion of self-creation and wore different masks publicly and privately. In 1968, Morrison admitted that his image as the Lizard King was “all done tongue-in-cheek.” He explained, “It’s not to be taken seriously. It’s like if you play the villain in a Western that doesn’t mean that’s you.” But the singer cautioned, “I don’t think people realize that.” Were these really different masks for Morrison, or did the true Jim get lost (or stuck) in the alcoholic stupor?

Before the band hit the big time, there were some musicians and hippies in Los Angeles who saw Jim as little more than a poseur, as someone who wanted to become part of the scene and yearned for attention and approval. They saw him not as a poet but as just another lost angel longing for fame and fortune in the City of Lights.

A foundational aspect of human life is the need to create meaning. People engage in this activity from birth, investigating and examining the world in relation to other people and things around them. This type of exploration is called semiotics, which in plain terms means asking what something means in relation to ourselves and others. From this vantage point, Morrison’s public persona was cast in symbolic terms, like how a celebrity/star acted and what they could get away with versus noncelebrities. When he yelled out, “I am the Lizard King…I can do anything!” it seemed he believed it—at least the version of Jim who had assumed that symbolic role.

People use symbols, then, to adapt to a complex world that contains an enormous amount of abstraction. Krieger pinned Morrison’s worldview on his antiauthority nature. “You couldn’t tell Jim Morrison what to do. And if you tried he would make you regret it,” the guitarist recalled. “He was forever rebelling against his navy officer father. Anyone who attempted to step into a role of authority over him became the target of his unresolved rage.” What he learned to lash out at was not his powerful father but those in authority who attempted to control him.

Psychotherapist Jeannine Vegh saw the lasting effects of growing up in a military family. “Jim suffered from a crisis in his mind. His words seem destined for a prophet, but, instead, he succumbed to drink and drugs. I assumed that he had been exposed to some form of family trauma.” She believes it may have been that his parents preferred “dressing down” to other forms of punishment. “When a child is berated and humiliated in front of others, it takes a toll on them spiritually, physically, and mentally.” The turmoil from this kind of upbringing is a clear factor in Jim basically disowning his parents even before he became famous. When his father told him that joining a band was stupid, he never forgave him and never spoke to him again.

Morrison, by studying film, literature, and sociology, understood more deeply and theoretically what his contemporaries like Jagger, McCartney, Lennon, and Joplin knew—fame served as one of many disguises he had to wear as a rock star. For Jim, there was the hyperindividual aspect of fronting a band and presenting himself to an audience and then there was the other piece of it, the communal vibe from the collective experience. That high from being on stage—the rush of emotion, the intensity, the energy—was likely another form of addiction for him.

When in his rock star guise, Jim could also turn into the hideous performer, especially when drunk. If Morrison didn’t feel or perceive what he wanted from the audience, he turned against them, essentially doing what he did in one-on-one relationships: goad and aggressively provoke a reaction—any reaction. “I don’t feel I’ve really done a complete thing unless we’ve gotten everyone in the theater on kind of a common ground,” he said. “Sometimes I just stop the song and just let out a long silence, let out all the latent hostilities and uneasiness and tensions before we get everyone together.”

Yet whether the show went well frequently depended on the other principal ingredient—alcohol. The booze distorted his perceptions, which the singer believed helped him reach new horizons, but the mixed-up sensitivities of an alcohol-addled mind washed out of him in ways that neither he nor the band completely understood. Misperception led to the attempted riot and arrest in New Haven and the beginning-of-the-end Miami incident.

Morrison realized and manipulated the power he possessed as rock star and purposely baited the crowd in ways that were new to them. A person going to a concert has expectations and understands (roughly) how they should act as a part of the community. The Doors, however, constantly messed with that pact because it titillated Jim’s worldview and allowed him to see both his true self and his growing authority after a lifetime of poking at the figures and institutions of power in his life. Morrison told a reporter: “I like to see how long they can stand it, and just when they’re about to crack, I let ’em go.”

Once questioned about what might happen to him if the crowd turned, even threatening his own safety, Jim responded in typical narcissistic fashion, claiming, “I always know exactly when to do it.” Rather than fear them or what they might do to him, he craved control over the masses. “That excites people…They get frightened, and fear is very exciting. People like to get scared.” Intensifying his controversial comments, he used sex as an analogy: “It’s exactly like the moment before you have an orgasm. Everybody wants that. It’s a peaking experience.” The domination over the crowd and its collective retort fascinated and mesmerized Morrison. He could directly influence their experience or lead the band into a frenzy—with Ray and Robby urging the emotional response while John pounded out a driving beat.

Examining Bob Dylan’s career, you can see similar uses of the mask metaphor as a way to make sense of complexity and abstraction. In the early 1970s, Dylan faced a period of agitation as he coped with the decline of his marriage to his wife Sara. Looking back on the period, he spoke about the many sides of himself that existed and kind of threw him off-kilter. Dylan explained: “I was constantly being intermingled with myself, and all the different selves that were in there, until this one left, then that one left, and I finally got down to the one that I was familiar with.”

To cope with fame, Dylan constantly created new personas and masks. He could alternatively exist as a singer, writer, musician, revolutionary, poet, degenerate, or any of the other labels that might be thrust at him. Dylan even spoke about himself in the third person to underscore the difference between him and the character named “Bob Dylan.”

Obviously, while there is ultimately a person there—waking each day, eating, working, daydreaming, bathing—there is another aspect of Dylan that defies simple definition. Dylan, a member of an elite category of iconic figures, exists outside his physical form and represents numerous meanings that give people a tool to interpret the world around them. As a result, the artist isn’t only a member of society but a set of interpretations and symbols that help others generate meaning. As fans and onlookers, people are familiar with this tradeoff. They accept it with each side gaining something in the exchange. A regular human being could never have handled the pressure of being called the spokesperson of a generation. Instead, Dylan used different personas to compartmentalize and make sense of it—until he snapped under the weight of drugs and booze and used a motorcycle accident in 1966 as an excuse to drop out. Some would call Dylan’s breakdown a natural result of a burden too heavy to carry.

The difference between Dylan and Morrison is that the latter died before he had to confront these many roles. In death, these roles are assigned to Morrison by fans, critics, historians, and observers. Both icons might ask—if possible—that we define them by the songs they created or the lyrics they wrote, but the larger culture wants so much more. There is an image that must be created, managed, and maintained. Once someone becomes famous or iconic, they hold two identities—symbol and person.

Yet according to Evan Palazzo of the Hot Sardines, the power of the music is the real testament to the Doors. “Imagine if you were a concert buff in 1968, 1969, 1970, the bands you could see live, it was unparalleled. We don’t have anything like that today,” he explains. “But if they were a new band, the Doors would blow everyone out of the water—it would be seismic.”

“Imagine if you were a concert buff in 1968, 1969, 1970, the bands you could see live, it was unparalleled. We don’t have anything like that today. But if they were a new band, the Doors would blow everyone out of the water—it would be seismic.”

For today’s listeners—no longer enslaved to vinyl, CD, or cassette because of the transformation to streaming music services—the Doors are just part of the Classic Rock genre. For younger listeners, the band is on a playlist or “decontextualized as a fifty-year-old band,” according to literary critic and writer Jesse Kavadlo. “My college students don’t experience music like we did pre-Internet. It’s just playlist stuff. All the music is available instantly, so they relate to it differently.”

It doesn’t even really matter that Jim is dead. For so many people, his spirit is as real as a brick wall, the latest Doors release on Spotify, or a video on YouTube.

***

“I tell you this man, I tell you this…I don’t know what’s gonna happen, man, but I wanna have my kicks before the whole shithouse goes up in flames.”

—Jim Morrison

A new look at Jim Morrison, the Doors, and the chaotic, turbulent 1960s!

MAY 1967 -- THE DOORS AND JIM MORRISON ROCK THE WHISKY!

In the months between “Break On Through” failing to make waves on the hit single chart and the July triumph of “Light My Fire” hitting number one, the Doors were just like every other band — trying to get noticed and establish a fan base. They had returned to the Whisky, the famed Los Angeles club where they had been the house opener in what seemed like just moments ago.

Read moreROADHOUSE BLUES NAMED 2023 INDEPENDENT PRESS AWARD BEST MUSIC BOOK

Cultural Historian Bob Batchelor Wins Independent Press Award® for Roadhouse Blues, Rollicking Tale of 1960s and 1970s America; Published by Hamilcar Publications

BOSTON & RALEIGH, March 20, 2023 – Shrouded in mystery and the swirling psychedelic sounds of the Sixties, the Doors have captivated listeners across seven decades. Jim Morrison—haunted, beautiful, and ultimately doomed—transformed from rock god to American icon. Yet the band’s full importance is buried beneath layers of mythology and folklore.

Cultural historian and biographer Bob Batchelor looks at the band and its significance in American history in Roadhouse Blues: Morrison, the Doors, and the Death Days of the Sixties (Hamilcar Publications).

Roadhouse Blues Wins 2023 IPA Book Award in Music

In recognition of the book’s excellence in writing, cover design, editorial production, and content, the Independent Press Award recognized Roadhouse Blues as the 2023 book award winner in the Music category. Selected IPA Award Winners are based on overall excellence among the tens of thousands of independent publishers worldwide. Roadhouse Blues is the third award Batchelor has earned from IPA.

“Roadhouse Blues is candid, authoritative, and a wonderful example of Batchelor’s absorbing writing style,” said Kyle Sarofeen, Founder and Publisher, Hamilcar Publications. “Taking readers beyond the mythology, hype, and mystique around Morrison, the book examines the significance of the band during a pivotal era in American history. Readers and reviewers have proclaimed that Roadhouse Blues is the most important book about the Doors ever written, just behind the memoirs of Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, and Robby Krieger.”

Cultural Historian Bob Batchelor Wins 2023 Independent Press Award — #GabbyBookAwards

“Independent publishing is pushing on every corner of the earth with great content,” said Gabrielle Olczak, Independent Press Award sponsor. “We are thrilled to be highlighting key titles representing global independent publishing.”

REVIEWS OF ROADHOUSE BLUES

“Fascinating, informative, extraordinary, and essential reading for the legions of Jim Morrison fans.” – Midwest Book Review

“Bob Batchelor writes with great eloquence and insight about the Doors, the greatest hard-rock band we have ever had, and through this book, we plunge deeply into the mystery that surrounds Jim Morrison. It is Batchelor’s warmth and compassion that ignites Roadhouse Blues and helps explain Morrison’s own miraculous dark fire.” – Jerome Charyn, PEN/Faulkner award finalist

“The most important book for Doors fandom since No One Here Gets Out Alive—and incomparably better! Grouped with Ray, Robby, and John’s books, this is the fourth gospel for fans of The Doors.” – Bradley Netherton, The Doors World Series of Trivia Champion and host of the podcast “Opening The Doors”

For more information, please visit independentpressaward.com. To see the list of IPA Winners, please visit: https://www.independentpressaward.com/2023winners

An excerpt “My Doors Memoir” is available at

https://hannibalboxing.com/excerpt-roadhouse-blues-morrison-the-doors-and-the-death-days-of-the-sixties/ (Open Access)

Hamilcar Publications

https://hamilcarpubs.com

Foreword by Carlos Acevedo

ISBN 9781949590548, paperback

ISBN 9781949590548, eBook

ABOUT BOB BATCHELOR

Bob Batchelor is the author of Roadhouse Blues: Morrison, the Doors, and the Death Days of the Sixties and Stan Lee: A Life. He has published widely on American cultural history, including books on Bob Dylan, The Great Gatsby, Mad Men, and John Updike. Rookwood: The Rediscovery and Revival of an American Icon, An Illustrated History won the 2021 IPA Award for Fine Art. The Bourbon King: The Life and Crimes of George Remus, Prohibition’s Evil Genius won the 2020 IPA Book Award for Historical Biography. Stan Lee: The Man Behind Marvel was a finalist for the 2018 Ohioana Book Award for Nonfiction.

Batchelor’s work has been translated into a dozen languages and appeared in Time, the New York Times, Cincinnati Enquirer, American Heritage, The Guardian, and PopMatters. He hosts “Deep Cuts” on the New Books Network podcast and is creator/host of the John Updike: American Writer, American Life podcast. He has appeared as an on-air commentator for National Geographic Channel, PBS NewsHour, BBC, PBS, and NPR. Batchelor earned a doctorate in Literature from the University of South Florida. He and his wife Suzette live in North Carolina with two wonderful teenage daughters. Visit him at www.bobbatchelor.com or on Facebook, LinkedIn, or Instagram.

Contact:

Kyle Sarofeen, Publisher, Hamilcar Publications

kyle@hamilcarpubs.com

OR

Bob Batchelor, bob@bobbatchelor.com

###

The Doors Explode into New York City -- March 1967

West Meets East When Doors Play Big Apple Shows, March 1967

New York City loved the Doors!

A handbill for the Doors concerts at Ondine!

After two early trips East to play New York City’s famous Ondine nightclub — well before they were famous — the Doors returned in March 1967 to a series of shows running through early April that would establish them as a favorite of fans and critics. The spark they received was a launchpad, especially in the dark days after “Break On Through” had been released (and fizzled on the pop charts) and prior to the national sensation that became “Light My Fire.”

On the third trip to NYC, the Doors intensified their mysticism and mystery for the celebrities and fame junkies that assembled at Ondine. While they had mainly been an underground hit on the two previous residencies, this time the press showed up too, eager to find out more about the psychedelic sounds emanating from Los Angeles and the beautiful singer who fronted the darkness.

Jim Morrison played up the differences between the coasts, which magnified his aura. As always, he spoke in proto-hippie lingo, but under a layer of foreboding. His words were sensuous and of the earth — heat, dirt, its elemental foundations.

“We are from the West. The world we suggest should be of a new Wild West. A sensuous, evil world. Strange and haunting…the path of the sun, you know.” — Jim Morrison

THE ONDINE AND NEW YORK HIPSTERS

The Ondine was a tiny club in Manhattan on Fifty-Ninth Street where celebrities and the city’s elite went to let loose. The hippest person on the scene was Andy Warhol, accompanied by his many acolytes and hangers-on — the beautiful people — but others included Jackie Kennedy, Jackie Gleason, and a horde of models, actors, and glam devotees.

The Ondine basically operated as a private discotheque long before disco would become all the rage. The raw environment brought together the rich, the wannabees, and others in a kind of fashionable speakeasy featuring go-go dancers, frenzied dance music, and an outrageous cast of characters. The basement locale was an odd place for ritzy socialites, basically tucked under a bridge in an ominous part of the city just three blocks from the East River. Similar to London Fog (where the Doors played in LA and created their famous sound), the club, named after the famous racing yacht Ondine, had a cramped stage that contrasted with its nautical theme.

The location of the Ondine nightclub today via Google Maps (March 2023)

Club manager Brad Pierce had been instrumental in getting the Doors booked for those early shows. Warhol later claimed that the band had gotten its break because a female deejay who had moved from LA knew the guys and urged Pierce to bring them east. To New York audiences, the Doors were billed as the hottest underground band in the nation and the LA connection helped establish that credibility. Enough people were bicoastal and had heard whispers about the group.

Everyone wanted to see the lead singer.

Of course, Jim met Warhol at the first run of shows. The iconic artist was reportedly so nervous about the encounter that he spent an evening mumbling to himself and awkwardly avoiding the singer. Eventually Warhol overcame his stage fright, probably at the sight of so many women mobbing Morrison while he stood at the bar between sets. “It was love at first sight on Andy’s part,” Ray said later.

BREAK ON THROUGH

Journalist Richard Goldsten took notice of the Doors and urged listeners to give the debut album a spin.

“Their initial album, on Elektra, is a cogent, tense, and powerful excursion. I suggest you buy it, slip it on your phonograph, and travel on the vehicle of your choice,” he explained. “The Doors are slickly, smoothly, dissonant. With the schism between folk and rock long since healed, they can leap from pop to poetry without violating some mysterious sense of form.”

From Goldstein’s perspective, the reason for the band’s success was its foundation in the blues. “This freedom to stretch and shatter boundaries make pretension as much a part of the new scene as mediocrity was the scourge of the old,” Goldstein wrote. “It takes a special kind of genius to bridge gaps in form. Their music works because its blues roots are always visible. The Doors are never far from the musical humus of America — rural, gut simplicity.”

What few could have imagined was that the Doors were on the verge of superstardom!

The band had seized the rippling current running through the Sixties, sucking in the joy and the darkness and spitting it out at audiences in a way that left listeners jubilant with the promise of good and bad, light and evil. The shows at the Ondine would be the last stretch before “Light My Fire” changed the band forever.

If the music pushed you hypnotically toward the edge of a cliff, Morrison stood ready to push. But you also felt that he was ready to jump too, plunging into worlds and universes unknown.

Roadhouse Blues: Morrison, the Doors, and the Death Days of the Sixties by cultural historian and biographer Bob Batchelor

Stan Lee Spreads the Gospel of Marvel Comic Books

Although Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four revolutionized the comic book industry, Stan Lee still felt the sting of working in a third-class business at a time when most adults thought comic books were aimed at children. What Lee realized, though, was that college students in the 1960s and 1970s were responding to Marvel in a new way — gleefully reading and re-reading the otherwordly antics of the costumed heroes.

Read moreWhen Robby Krieger Met Jim Morrison!

Fans of the Doors and rock ‘n roll history lovers have been waiting decades for Robby Krieger — Doors guitarist and songwriter extraordinaire — to write a memoir of his days and nights in America’s iconic rock band. Set the Night on Fire: Living, Dying, and Playing Guitar With the Doors came out in October 2021, but the paperback is set to publish October 25, 2022.

Read moreStan Lee on Cameos and Superheroes

Five Years Ago: Creating Superheroes and Cameos

Kids, teenagers, and adults of all ages got weak in the knees around Marvel icon Stan Lee. Yet, talking to them moments after meeting him, you could hear the joy in their voices. Some shed tears of happiness. Universally, they looked frozen in the moment of delight — as if they were opening Christmas presents or getting ready to blow out candles on their birthday cake.

I chatted with a 50-something father who confessed that taking his teen daughter to meet Stan was a bucket list kind of event, one that they were able to share together. He wiped tears from his eyes as he reminisced about watching Marvel films with his daughter and how Lee’s cameos were a bonding moment for them.

Stan Lee on cameos in Marvel films

These clips are from a September 26, 2017 newspaper piece on Stan's appearance at a comic book convention in Madison, Wisconsin, (about a year before he died).

The sentiment demonstrates his significance as the symbol of Marvel and Marvel Studios for so many fans. There has never been a phenomenon quite like Stan’s cameo roles. His brief blip on the screen frequently caused the audience to break out in applause. For many fans, the cameo was as necessary and elemental as the film itself. One could not exist without the other.

Anyone else remember going to a Marvel film and hearing spontaneous applause when Stan's cameo rolled?

Stan Lee's co-created superheroes an inspiration

Stan Lee's co-created superheroes have served as an inspiration for generations because he gave them human traits. This idea — so novel in the early 1960s — caught fire during an era where novelists, screenwriters, and others were challenging conventional norms about what it meant to be a superhero.

Learn more about Stan’s epic tale in Stan Lee: A Life (Rowman & Littlefield).

Stan Lee: A Life by historian and biographer Bob Batchelor

Young Readers Edition of Stan Lee Biography

In this young adult edition of Stan Lee: The Man Behind Marvel, award-winning cultural historian Bob Batchelor offers an in-depth and complete look at this iconic visionary. Batchelor explores how Lee, born in the Roaring Twenties and growing up in the Great Depression, capitalized on natural talent and hard work to become the editor of Marvel Comics as a teenager. Lee went on to introduce the world to heroes that were complex, funny, and fallible, just like their creator and just like all of us.

Read moreOnly 10 Days Until 100th Anniversary of Prohibition!

Only 10 Days Until 100th Anniversary of Prohibition!

On January 17, 2020, the nation went dry...at least legally!

Media Alert: 100th Anniversary of Volstead Act Implementation Centennial of Law that Launched Prohibition and the Roaring Twenties, Rampant Lawlessness, American citizens transformed into Criminals

This is a once-in-a-lifetime chance to examine the day the nation went dry and the tremendous consequences it had on the rest of American history.

What: The Volstead Act, enacted into law on October 28, 1919, defined the parameters of the Eighteenth Amendment. By passing the Volstead Act, Congress formally prohibited intoxicating beverages; regulated the sale, manufacture, or transport of liquor; but still ensured that alcohol could still be used for scientific, research, industrial, and religious practices.

When: Congress voted to overrule President Woodrow Wilson’s veto, passing the Volstead Act on October 28, 1919. Legal enforcement of Prohibition began on January 17, 1920.

Why: Chaos reigned in the early twentieth century. In America, the tumultuous era included millions of immigrants streaming into the nation, and then a protracted war that seemed apocalyptic. The backlash against the disarray sent some forces searching for normality. Liquor was an easy target. Supporters of dry law turned the consumption of alcohol into an indicator of widespread moral rot.

Bob Batchelor, author of The Bourbon King: The Life and Crimes of George Remus, Prohibition’s Evil Genius (Diversion Books) is available for commentary and discussion of Prohibition and the Roaring Twenties. The Bourbon King is the epic tale of “Bootleg King” George Remus, who from his Gatsby-like mansion in Cincinnati, created the largest illegal liquor ring in American history. In today’s money, Remus built a bourbon empire of some $5 to $7 billion in just two and a half years.

People all over the world know the name “Al Capone,” but without George Remus and his pipeline of Kentucky bourbon, there may never have been a Capone. Although largely forgotten today, Remus was one of the most famous men in American in the 1920s, including the shocking murder of his wife Imogene and subsequent high-stakes trial that set off a national sensation.

QUOTES:

George Remus: “My personal opinion had always been that the Volstead Act was an unreasonable, sumptuary law, and that it never could be enforced.”

George Remus: “I knew it [the Volstead Act] was as fragile as tissue paper.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald: “America was going on the grandest, gaudiest spree in history…The whole golden boom was in the air—its splendid generosities, its outrageous corruptions and the tortuous death struggle of the old America in prohibition.” From the essay “Early Success” (1937)

Bob Batchelor: “Prohibition turned ordinary citizens into criminals. Media attention turned some criminals into Jazz Age icons. At the top of the heap stood those few, like George Remus, who took advantage of the new illegal booze marketplace to gain untold power and riches.”

Bob Batchelor: “During Prohibition, ‘bathtub gin’ often contained substances that were undrinkable at best and deadly at worst. A band of rumrunners selling ‘Canadian’ whiskey were actually peddling toilet bowl cleaner. Tests on booze obtained in one raid revealed that the liquor contained a large volume of poison.”

Bob Batchelor: “Remus may have been singularly violent and dangerous, but his utter disregard for Prohibition put him in accord with how much of American society felt about the dry laws. Within the government, the lack of resolve for enforcing Prohibition started at the top with President Warren G. Harding and his corrupt administration.”

“Bob Batchelor’s The Bourbon King: The Life and Crimes of George Remus, Prohibition’s Evil Genius might as well be the outline of a Netflix or HBO series.”

– Washington Independent Review of Books

Two interviews that provide an overview conducted with national, well-respected interviewers:

https://www.iheart.com/podcast/53-history-author-show-27301458/episode/bob-batchelor-the-bourbon-king-49050931/

https://soundcloud.com/leonard-lopate/bob-batchelor-on-his-book-the-bourbon-king-about-infamous-bootlegger-george-remus-9319

ABOUT BOB BATCHELOR

C-SPAN 2’s Book TV:

https://www.c-span.org/video/?464406-1/the-bourbon-king

Bob Batchelor is a critically-acclaimed, bestselling cultural historian and biographer. He has published widely on American history and literature, including books on Stan Lee, Bob Dylan, The Great Gatsby, Mad Men, and John Updike. Bob earned his doctorate in English Literature from the University of South Florida. He teaches in the Media, Journalism & Film department at Miami University (Oxford, Ohio) and lives in Blue Ash, Ohio.

ABOUT THE BOURBON KING

Critics have called The Bourbon King "riveting," "definitive," and "rollicking," among other accolades. This is THE story of Jazz Age Criminal mastermind George Remus!

“The fantastic story of George Remus makes the rest of the ‘Roaring Twenties’ look like the ‘Boring Twenties’ in comparison. It’s all here: murder, mayhem—and high-priced hooch.”

—David Pietrusza, author of 1920: The Year of the Six Presidents

“Guns, ghosts, graft (and even Goethe) are all present in Bob Batchelor’s meticulous account of the life and times of the notorious George Remus. Brimming with liquor and lust, greed, and revenge, this entertaining book might make you reach for a good, stiff drink when you’re done.”

—Rosie Schaap, author of Drinking with Men

“The Bourbon King is a much-needed addition to the American mobster nonfiction bookshelf. For too long, George Remus has taken a backseat to his Prohibition-era gangster peers like Lucky Luciano and Al Capone. Read here about a man who intoxicated the nation with a near-endless supply of top-shelf Kentucky bourbon, and then got away with murder.”

—James Higdon, author of The Cornbread Mafia: A Homegrown Syndicate’s Code of Silence and the Biggest Marijuana Bust in American History

“Al Capone had nothing on George Remus, the true king of Prohibition. His life journey is fascinating, a Jazz Age cocktail that Bob Batchelor mixes for readers within these pages. Remus went from pharmacist to high-profile defense attorney to bourbon king to murderer.”

—Tom Stanton, author of Terror in the City of Champions: Murder, Baseball, and the Secret Society That Shocked Depression-Era Detroit