Filled with mayhem, mountains of illicit cash, and rivers of bourbon, “Tales of the Bourbon King” presents the life and crimes of George Remus, bootleg king of the Jazz Age, a dazzling true crime spectacle. With gunfights and fisticuffs, he turned America into his violent playground, grafting his way into Warren Harding’s White House. A model for Jay Gatsby, Remus’s story epitomizes the spectacular 1920s – until it came crashing down in an improbable tale of deceit and rage, centered on the dastardly G-man who stole his wife, leading directly to a fateful gunshot that ended her life.

Read more100 Years Ago: Prohibition Becomes Law with Volstead Act

The Hamilton Daily News Announces Passage of “Dry Bill”

On October 28, 1919, the Senate voted to override the veto of President Woodrow Wilson. The United States would become a dry nation after ratification of the law in January 1920.

The Volstead Act, enacted into law on October 28, 1919, defined the parameters of the Eighteenth Amendment. By passing the Volstead Act, Congress formally prohibited intoxicating beverages; regulated the sale, manufacture, or transport of liquor; but still ensured that alcohol could still be used for scientific, research, industrial, and religious practices.

Legal enforcement of Prohibition began on January 17, 1920.

Chicago Tribune Editors Have Fun with a Witty Headline

Why Did the US Go Dry?

Chaos reigned in the early twentieth century. In America, the tumultuous era included millions of immigrants streaming into the nation, and then a protracted war that seemed apocalyptic. The backlash against the disarray sent some forces searching for normality. Liquor was an easy target. Supporters of dry law turned the consumption of alcohol into an indicator of widespread moral rot.

Bob Batchelor, author of The Bourbon King: The Life and Crimes of George Remus, Prohibition’s Evil Genius (Diversion Books) is available for commentary and discussion of Prohibition and the Roaring Twenties. The Bourbon King is the epic tale of “Bootleg King” George Remus, who from his Gatsby-like mansion in Cincinnati, created the largest illegal liquor ring in American history. In today’s money, Remus built a bourbon empire of some $5 to $7 billion in just two and a half years.

October 28, 1919, Headline in the Chicago Tribune

Quotes:

George Remus: “My personal opinion had always been that the Volstead Act was an unreasonable, sumptuary law, and that it never could be enforced.”

George Remus: “I knew it [the Volstead Act] was as fragile as tissue paper.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald: “America was going on the grandest, gaudiest spree in history…The whole golden boom was in the air—its splendid generosities, its outrageous corruptions and the tortuous death struggle of the old America in prohibition.” From the essay “Early Success” (1937)

Bob Batchelor: “Prohibition turned ordinary citizens into criminals. Media attention turned some criminals into Jazz Age icons. At the top of the heap stood those few, like George Remus, who took advantage of the new illegal booze marketplace to gain untold power and riches.”

Bob Batchelor: “During Prohibition, ‘bathtub gin’ often contained substances that were undrinkable at best and deadly at worst. A band of rumrunners selling ‘Canadian’ whiskey were actually peddling toilet bowl cleaner. Tests on booze obtained in one raid revealed that the liquor contained a large volume of poison.”

Bob Batchelor: “Remus may have been singularly violent and dangerous, but his utter disregard for Prohibition put him in accord with how much of American society felt about the dry laws. Within the government, the lack of resolve for enforcing Prohibition started at the top with President Warren G. Harding and his corrupt administration.”

The Bourbon King

“Bob Batchelor’s The Bourbon King: The Life and Crimes of George Remus, Prohibition’s Evil Genius might as well be the outline of a Netflix or HBO series.”

– Washington Independent Review of Books

92 Years Ago Today -- George Remus Murders Imogene in Cincinnati's Eden Park

92 years ago in 1927, George Remus murdered his wife Imogene in Eden Park, just outside Cincinnati.

The gunshot that indian summer morning capped a tumultuous period of mayhem, betrayal, and embezzlement. The subsequent trial would be followed by millions worldwide!

The accompanying February 1928 insanity trial transcripts provide insight into what Remus thought about his wife and the murder.

Below is a portion of the February 1928 insanity hearing transcript. Remus answers questions about his early days with Imogene and admits that they engaged in “illicit relations.”

February 1928 insanity hearing transcript — George Remus answers questions about his early days with Imogene — “illicit relations”

Remus admits that he hoped to catch Imogene and Franklin Dodge together — so he could kill them both!

Remus admits that he hoped to catch Imogene and Franklin Dodge together — so he could kill them both!

George claimed he married Imogene to bring her up from poverty…and that she owed him as a result. The betrayal with Dodge was too much. The affair and that it became common knowledge in the criminal underworld, disgraced him, and — in his mind — forced action.

George claimed he married Imogene to bring her up from poverty…and that she owed him as a result. The betrayal with Dodge was too much…

Given his ability to manipulate juries, Remus declared he would defend himself, giving him direct access to the 12 people who held his life in their hands.

Given his ability to manipulate juries, Remus declared he would defend himself, giving him direct access to the 12 people who held his life in their hands.

5 Minutes to Murder: George Remus, The Bourbon King

5 Minutes to Murder: George Remus, The Bourbon King

Historian Bob Batchelor discusses The Bourbon King outside the former Cincinnati hotel where "Bootleg King" George Remus stalked his wife Imogene, before murdering her in cold blood at Eden Park.

The Bourbon King, The Inside Story: Government Corruption, Then and Now

A popular political cartoon representing how the nation has been crushed under the weight of the Teapot Dome scandals.

Widely considered the “best dressed man in Washington,” Jess Smith served as Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty’s confidante, friend, nurse, and bagman for the mountains of cash he was able to extort from America’s bootleg barons. When he committed suicide on May 30, 1923, it ended what little hope Remus had from staying out of jail.

The Bourbon King offers a window into government corruption at the highest levels. Any lessons we can learn for understanding today’s political scene?

Presidential corruption is a delicate matter. Incredibly partisan, one side sees something that the other does not. History helps sort out details and brings new evidence to light, but then how do we deal with scandal as it takes place?

George Remus built a far-reaching bribery network that stretched from the suburban Cincinnati police to the Harding White House. He virtually taught Newport, Kentucky, about graft, which enabled the city to become a model for corruption and vice. Decades later, the mafia would move into Newport and see the city as a model for Las Vegas.

Much of the corruption Remus took advantage of came directly from the Prohibition Bureau, particularly as enforcement began. At every level, “Prohis" (the nickname given to agents tasked with enforcing Prohibition) fell to corruption and payoffs.

For example, many leaders at the state level issued whiskey certificates—paper documents that gave the holder the ability to sell liquor legally to pharmacies, hospitals, doctors, and others for “medicinal usage”—for a hefty fee.

“They received considerations,” Remus explained. “Otherwise those withdrawals would never have come to the respective distilleries that I was owner of.”

As a result of the permutations, trust evaporated and criminality ruled, particularly as officials in the Harding administration learned that they could be so dishonest.

Much of the underhanded maneuvers originated in Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty’s office and ran through Jess Smith, his bon vivant friend and confidante. Jess ran interference for Daugherty and his Ohio cronies linked to Harding’s White House. The money changed hands, which fit with Remus’s worldview of how men acted when they had a deal, but he had no guarantee that Smith could do what he said.

Amidst this setting, and with his own loose lips, could Remus possibly keep his central bribe secret? A journalist reported that he heard a rumor around town about George, explaining, “He was once heard to boast that he was immune from prosecution because he had the ear of the private secretary of a cabinet officer.”

The bribery network soon crumbled…

On May 30, 1923, Jess startled awake in the middle of the night. He drew a pistol from a bedside drawer, stumbled to the bathroom, and lay down on the floor. Positing his head on the side of a wastebasket, Jess put the revolver to his temple and pulled the trigger.

Smith killed himself a little more than two months before the shocking death of Warren G. Harding, who declined quickly on a trip out West and ultimately passed away on August 2, 1923, only 57 years old.

The Ohioan was wildly popular at the time and mourners lined the train route that brought the dead president back to the nation’s capital. Only after his death would the full weight of his scandal-ridden administration become unraveled by a series of congressional investigatory committees and reporters hot on the trail of his Cabinet members and their cronies, many who seemed to specialize in corruption. For George, the deaths of Smith and Harding left him with little hope. Worse, the tragedies severed his ties to Daugherty.

“Misfortune came fast, suddenly,” Remus said. “Jess Smith was found dead in his bathroom. President Harding died. The Senate called for the impeachment of Harry Daugherty. The game was over. I had no place to turn.”

Shortly after President Harding died in office, many scandals came to light that revealed the full extent of his administration’s corruption. However, Harding was given a kind of free pass.

Today, with President Donald Trump, the accusations regarding corruption are much more vocal and public. Events that transpired in Harding’s era demonstrated how bad actors could really line their own pockets by using their power in various schemes.

Modern presidents are not given the same benefit of the doubt. The amplification of outrage based on social media and a more pervasive news cycle means that cries of government corruption are going to be louder and shriller.

The challenge for us today is attempting to determine how much of the dishonesty is real and what might be condensed down to partisanship. Calvin Coolidge — Harding’s successor — watched a series of Congressional investigations into corruption by Harding Cabinet members. He constantly worried about how those spectacles would influence voters’ minds in the 1928 election.

As long as the economy boomed, observers gave Harding and Coolidge a free pass. At the time, the scandals did not topple their administrations.

Today, however, the notion of a free pass is laughable as a president’s every move is scrutinized by a highly-partisan citizenship.

The media—crippled by the financial crisis that has left the industry in shambles over the last two decades—responds by chasing every sensational detail, forced to feed the bile back to consumers, hoping that their anger will result in advertising dollars and measured in online “impressions.”

The corruption of the Harding administration—with George Remus at its center—provides a case study in corruption by White House subordinates who realized how swiftly they could fleece the system. Today, are we too distracted by the daily shouting to scrutinize the details as they unfold just below the surface?

The Bourbon King, The Inside Story: Prohibition and Marijuana

Can we learn from Prohibition in thinking about issues regarding the legalization of marijuana?

My favorite history books provide deep insight the issues of the past and act as a kind of guide for addressing contemporary concerns. I had this idea in mind when writing The Bourbon King — how do we think about marijuana and other lifestyle choices regulated and legislated by the government?

We are still learning the lessons of Prohibition a century later. The most destructive aspect of the dry era was that it took a significant human toll on America.

Many lives were wasted, from people poisoned by tainted alcohol to those killed in enforcing the Volstead Act or attempting to circumvent the law. We have seen similar scenarios play out over the last several decades with marijuana legislation and enforcement.

During Prohibition and with weed over the last several decades, a significant air of lawlessness became commonplace. The nation still deals with these issues now. For instance, people travel between states that have legalized recreational and medical marijuana and those that still criminalize it.

Texas Senator Morris Sheppard, the “father of Prohibition”

We are still learning the lessons of Prohibition a century later…Many lives were wasted…a major human toll on America…We have seen similar scenarios play out over the last several decades with marijuana legislation and enforcement.

The Bourbon King, The Inside Story: George Remus and Al Capone

How does George Remus compare to Al Capone?

Without George Remus, there is no Al Capone.

Every city in America had underworld operatives long before Prohibition. Bootlegging existed, whether it was running the product of home stills to avoid government taxes or bringing cheap liquor into the United States from Mexico.

When the dry laws kicked in, rumrunning became big business. In America’s largest cities, like Chicago, bosses like Johnny Torrio quickly realized that America’s thirst needed quenched and by smuggling liquor, they could make untold millions.

Rather quickly, criminal kingpins realized that they needed booze to thrive. Remus provided that liquor and enabled men like Torrio, and his successor Al Capone to create empires. Other liquor masterminds existed, so Remus was not alone in getting booze to mob bosses, but his network was extensive and centered on selling the highest quality Kentucky bourbon.

Selling “the good stuff” led to connections between Torrio’s Windy City operation and Remus’s headquarters at Death Valley. George Conners, Remus’s top lieutenant, spoke at length about his salesman trips to Chicago to funnel bourbon into the large market there. Torrio also had ties to the Cincinnati metro area, marrying a woman from Northern Kentucky and having family in the area.

While George and Al had similar interests in selling booze and making as much money as possible, on a personal level, Remus was a generation older than Capone and some of the other “name” mafia bosses, like Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky, the friends who operated at the feet of criminal mastermind Arnold “the Big Brain” Rothstein in New York City. After Rothstein’s murder, Luciano and Lansky became kingpins themselves. Men like these were career criminals. When bootlegging turned vicious, they were more willing to kill or incite violence and murder to achieve their end goals.

Remus, although no stranger to gunfights or ordering his men to protect his product with gun play, was a product of the Gilded Age. George’s first instinct was to respond to a threat with his fists or the gold-tipped, weighted cane that he carried as both a style statement and weapon. As Prohibition went on, it became a shoot-first world.

People often ask why Remus didn’t get back into bootlegging in June 1928 after his stints behind bars and at the Lima State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. There are many potential answers, but most directly: without money or henchmen, Remus could not reestablish his bourbon empire after winning his freedom. George would have needed an army to reclaim even a portion of his empire, but after Imogene and Franklin Dodge decimated his fortune, he could not afford to rebuild.

This is only a small tidbit of the complexity of Remus’s interactions with his mafioso colleagues. The full story will make more sense after reading The Bourbon King.

The famous Rathskeller bar in the Seelbach Hilton Hotel in downtown Louisville. Allegedly, Remus and Capone drank together at the Rookwood Pottery tile-encrusted grotto, one of the most stunning displays of Rookwood from the early twentieth century.

The Bourbon King, The Inside Story: George Remus as a Business Leader

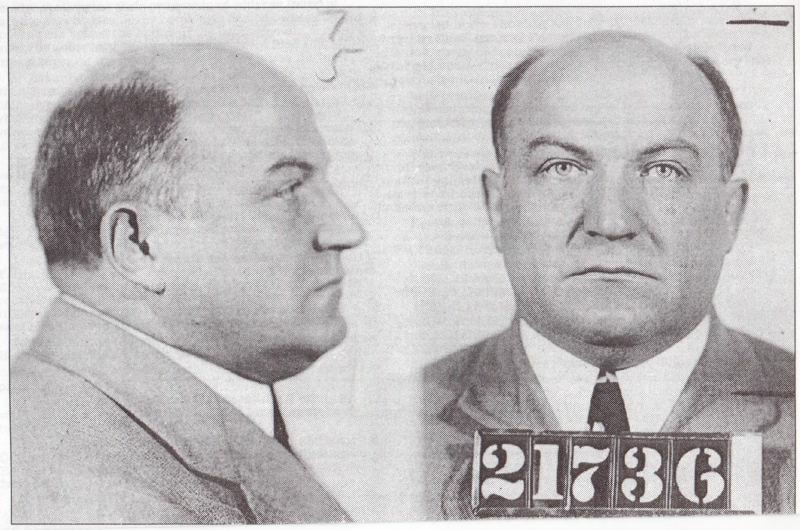

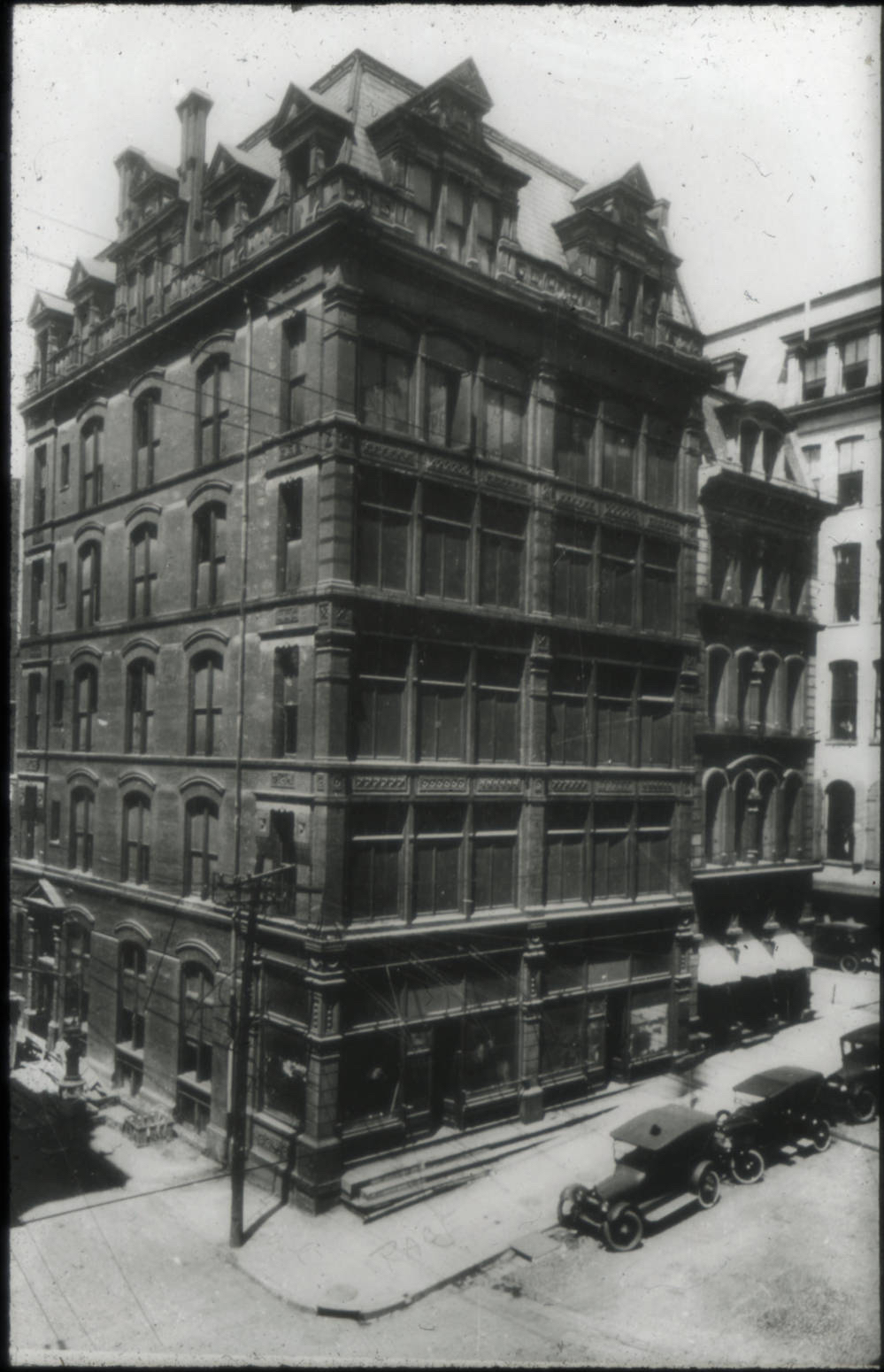

At the height of his power, George Remus purchased an office complex at 225 Race Street on the southwest corner of Race and Pearl Streets, renaming it the “Remus Building.” The lobby tile display (allegedly from the famous Rookwood Pottery) spelled out “Remus,” which he thought demonstrated his authority. For his second-floor office space, Remus spent $75,000 on lavish furniture, accessories, and equipment, as well as a personal chef.

(Courtesy Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, Cincinnati History Slide Collection)

George Remus as a Business Leader

Remus cashed out in Chicago and took his fat stacks to Cincinnati, the epicenter of the bourbon and beer industries in the early twentieth century. He parlayed his life earnings into a fortune that some estimate reached $200 million, which would be many billions of dollars today over the course of about two and a half years.

Remus realized that he could control every aspect of the bootlegging business, from production to distribution via other rumrunners and liquor operatives, while also selling directly to consumers. He called this idea “the circle,” which was probably modeled on what J. D. Rockefeller had done in the oil business. “Cornering the market” was a popular idea in the 1920s, a decade and a half after President Theodore Roosevelt had criticized business leaders for attempting to create corporate monopolies.

“Remus was to bootlegging what Rockefeller was to oil.”

— Paul Y. Anderson, St. Louis Dispatch

Basically, like Rockefeller in oil or J. P. Morgan in steel, George wanted to create a network that controlled all aspects of the bourbon industry, from creating the product in Kentucky distilleries to shipping and distribution, and then through the sales process. If he controlled all these points—thus creating the circle—he would dominate the market.

Creating this national network took a lot of money and a lot of hubris. Remus had both in spades. He pulled it off, but in the end, faced some of the same challenges businesses have always faced: lack of talent to manage the organization and deals that fell through. Remus needed henchmen that were as smart as him and he had trouble finding them. Then, his “sugaring” network—the term for bribery in the 1920s—fell through. These challenges essentially put him out of business.

Check out The Bourbon King: The Life and Crimes of George Remus, Prohibition’s Evil Genius for the whole story, including how Remus assessed his own abilities as a corporate leader.

The Bourbon King, The Inside Story: The Birth of a Bootleg King

How did George Remus become “Bootleg King?” What drove him to criminality—Hubris? Greed? Love of alcohol?

George Remus moved decisively into bootlegging.

As Remus’s legal career flourished, he became celebrity in Chicago, then nationally. [I like to joke that he was kind of the Johnnie Cochran of early twentieth century Chicago.] The fame and money were not enough to satisfy his desires — he expected to become a larger than life figure. Remus thought of himself in almost presidential terms, as if he were anointed to greatness.

Remus began defending small-time Windy City bootleggers in his law practice. Like court employees, attorneys, and probably even the judges themselves, George looked on bemused when these hoodlums would pay fines by pulling large rolls of cash out of their pockets and quickly counting out huge sums of money. Rolls of hundreds…

Legend has it that Remus realized if the two-bit thugs could make thousands of dollars, then he could use his intelligence to make millions.

As a top defense attorney, George’s annual salary reached more than ten times the cost of the average home in America, but he wanted more…more fame, money, and the toys the good life made possible.

Remus had no moral position on bootlegging or breaking the law. He often claimed to be a teetotaler, but many witnesses could have testified to that standing as yet another Remus “little white lie.” He liked to share a stiff drink and a fat, black cigar with friends, despite the public histrionics about not drinking liquor.

George needed to play intellectual games to justify his positions on various issues. For example, he believed that acting outside the bounds of decorum in court battles was okay, because doing so enabled him to spare his clients the death sentence. The end goal made the means of attaining it justified in his mind.

Similarly, Remus didn’t think Prohibition was a just cause. His early attempts at bootlegging in Chicago proved that enforcement was difficult and that people would continue to demand liquor, regardless of the law.

George also knew that the money would give him power and influence. He set out to exploit the loopholes in the Volstead Act as a way to fulfill the flashy life he dreamed of…and his young paramour Imogene Holmes yearned for her entire life.

The Bourbon King, The Inside Story: Why Write about George Remus

How did you discover the story of George Remus, and why did you decide to write a book about him?

Imagine having a topic in your head for 17 years!

I stumbled across George Remus about 17 years ago when Stanley Cutler, an esteemed American historian and scholar, asked me to write about bootlegging for the Dictionary of American History.

Remus’s story was so epic that I couldn’t get it out of my mind. The “Bootlegging” entry had to be concise, so I didn’t get much of an opportunity to expand on the Remus story, but I snuck him in, as well as mentions of Cleveland and Pittsburgh.

Here’s that bit from the essay:

Given the pervasive lawlessness during Prohibition, bootlegging was omnipresent. The operations varied in size, from an intricate network of bootlegging middlemen and local suppliers, right up to America's bootlegging king, George Remus, who operated from Cincinnati, lived a lavish lifestyle, and amassed a $5 million fortune. To escape prosecution, men like Remus used bribery, heavily armed guards, and medicinal licenses to circumvent the law. More ruthless gangsters, such as Capone, did not stop at crime, intimidation, and murder.

— “Bootlegging” Dictionary of American History, 2003

Although researched and written so long ago, I still see bits of my personal writing style that persists. “Pervasive lawlessness” is a stylistic point, as well as the pacing of the sentence.

Later, in 2013, I published a biography of The Great Gatsby, which I had been researching and writing for years. Obviously, the work on the book forced me to continue thinking about this crazy bootleg king, particularly since so many people began writing that he was the inspiration for Jay Gatsby, rather than just one of several.

[Spoiler alert: the link between Jay Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and George Remus is an important discussion in The Bourbon King and the beginning of one of America’s great literary mysteries that readers will really enjoy.]