Stan Lee: A Life Well-Lived -- Excelsior!

“Lee became Marvel madman, mouthpiece, and all-around maestro – the face of comic books for six decades. The man who wanted to pen the Great American Novel did so much more. Without question, Lee became one of the most important creative icons in contemporary American history.”

— Bob Batchelor, author, Stan Lee: The Man Behind Marvel

Read moreThe Black Knight Debuts in 1955

“Strike, black blade! The Black Knight challenges Modred the Evil!”

Mixing the legendary tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table with elements from superhero lore, Stan Lee and his favorite artist Joe Maneely cocreated The Black Knight for Atlas Comics, debuting in May 1955.

Lee and Maneely took a risk in bringing out the new hero, despite the enduring popularity of King Arthur for centuries. Superhero comic books were basically out of favor in the 1950s, thanks to the ravings of lunatic psychiatrist Frederic Wertham and countless adults who believed his diatribes against the industry, particularly that reading comic books paved the path to juvenile delinquency.

Wertham’s backlash had sent the publishing industry reeling, forcing many companies into bankruptcy. If you didn’t work at a publisher named DC or have characters like Superman and Batman, then turning to other genres proved the only way to stay afloat.

The artistic duo’s creation featured a powerful, armored hero who hid behind a secret identity (the meek Sir Percy of Scandia) so that he could thwart wrongdoers. The Black Knight worked with famed magician Merlin to protect and defend King Arthur's Camelot from the schemes of Modred the Evil.

In the post-Wertham environment, publisher Martin Goodman and editor Lee fiddled with the comic book lineup, attempting to find the right mix that readers would buy. At that time, however, superheroes were out at Atlas. Even the mighty Sub-Mariner would be cancelled in October 1955 with Sub-Mariner #45.

Despite how much the artistic duo of Lee and Maneely loved the Black Knight character, the series only lasted five issues, folding with the April 1956 cover dated copy. Instead, the company moved to cowboy comics, suspense series, and Hollywood tie-ins in an attempt to wrangle the fickle marketplace. Atlas' place on the newspaper stands would feature titles like World Of Fantasy, World of Mystery, and old favorites like Millie The Model.

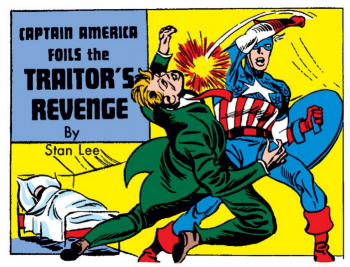

Stan Lee’s First Publication – Captain America Comics #3 (1941)

Joe Simon needed copy and he needed it fast!

The Timely Comics editorial director and his coworker and friend Jack Kirby were hard at work on the hit they had recently launched – the red, white, and blue hero Captain America. Readers loved the character and Simon and Kirby scrambled to meet the demand.

The Captain America duo brought in some freelancers to keep up. Then they threw some odd copy-filler stories to their young apprentice/office boy Stanley Lieber as a kind of test run to see if the kid had any talent. He had been asking to write and the short story would be his on-the-job audition.

The throwaway story that Simon and Kirby had the teenager write for Captain America Comics #3 (May 1941) was titled: “Captain America Foils the Traitor’s Revenge.” The story also launched Lieber’s new identity as “Stan Lee,” the pseudonym he adopted in hopes of saving his real name for the future novel he might write.

Given the publication schedule, the latest the teen could have written the story is around February 1941, but he probably wrote it earlier. The date is important, because it speaks to Lieber’s career development. If he joined the company in late 1939, just after Kirby and Simon and when they were hard at work in developing Captain America, then there probably wasn’t much writing for him to do. However, if the more likely time frame of late 1940 is accepted, then Lieber was put to work as a writer fairly quickly, probably because of the chaos Simon and Kirby faced in prepping issues of Captain America and their other early creations, as well as editing and overseeing the Human Torch and Sub-Mariner efforts.

Lee later acknowledged in his autobiography that the two-page story was just a fill-in so that the comic book could “qualify for the post office’s cheap magazine rate.” He also admitted, “Nobody ever took the time to read them, but I didn’t care. I had become a published author. I was a pro!” Simon appreciated the teen’s enthusiasm and his diligence in attacking the assignment.

An action shot of Captain America knocking a man silly accompanied Lieber’s first publication for Simon and Kirby. The story – essentially two pages of solid text – arrived sandwiched between a Captain America tale about a demonic killer on the loose in Hollywood and another featuring a giant Nazi strongman and another murderer who kills people when dressed up in a butterfly costume. “It gave me a feeling of grandeur,” Lee recalled at the 1975 San Diego Comic-Con.

While many readers may have overlooked the text at the time, its cadence and style is a rough version of the mix of bravado, high-spirited language, and witty wordplay that marked the young man’s writing later in his career.

Lou Haines, the story’s villain, is sufficiently evil, although we never do find out what he did to earn the “traitor” moniker. In typical Lee fashion, the villain snarls at Colonel Stevens, the base commander: “But let me warn you now, you ain’t seen the last of me! I’ll get even somehow. Mark my words, you’ll pay for this!”

In hand-to-hand combat with the evildoer, Captain America lands a crippling blow, just as the reader thinks the hero may be doomed. “No human being could have stood that blow,” the teen wrote. “Haines instantly relaxed his grip and sank to the floor – unconscious!” (Captain America Comics #3, p. 37) The next day when the colonel asked Steve Rogers if he heard anything the night before, Rogers claims that he slept through the hullabaloo. Stevens, Rogers, and sidekick Bucky shared in a hearty laugh.

The “Traitor” story certainly doesn’t exude Lee’s later confidence and knowing wink at the reader, but it clearly demonstrates his blossoming understanding of audience, style, and pace.

Both “Stan Lee” and a career were launched!

Stan Lee Sues Marvel…And Wins!

In a tale filled with greed, envy, unfulfilled promises, and years of legal scheming, Marvel announced a financial settlement on April 28, 2005, with its most famous employee – comic book legend Stan Lee.

Filed under the heading, “Things No One Ever Expected,” Lee had sued Marvel three years earlier for not fulfilling the terms of his employment contract. The subsequent legal maneuvering created a tense situation for Lee and a public relations headache for the company he had helped build.

The beguiling battle began in late October 2002, when the popular CBS news program 60 Minutes II aired a segment about the state of comic books and the tremendous popularity of superhero films. The report also examined Lee’s potential skirmish with Marvel regarding language in his contract, specifically certain payments Lee justly deserved based on the surging box office returns of Marvel films after decades of mediocre efforts and failed attempts at bringing the company’s superheroes to the screen.

The new program painted Marvel in an evil light – a greedy corporation making insane amounts of money off the backs of its writers and artists. Lee’s 1998 contract seemed straightforward, but when it was inked no one expected the future to include such wildly successful films – X-Men (2000) earned nearly $300 million worldwide, while Spider-Man (2002) became a global phenomenon, drawing some $821 million.

60 Minutes II correspondent Bob Simon, using a bit of spicy language that seemed uncharacteristic for the venerable CBS show, actually asked Lee if he felt “screwed” by Marvel. Lee toned down his usual bombast though and displayed remorse for having to sue his employer, a situation that he explained “I try not to think of it.” As a result, many Marvel fans sided with Lee in the dispute.

Mere days after the segment aired, Lee sued Marvel for not honoring a stipulation that promised to pay him 10 percent of the profits from Marvel Enterprise film and television productions. Despite his $1 million annual salary as chairman emeritus, Lee’s attorney’s argued that the provision be honored. The grand battle between Marvel and its most famous employee shocked observers and sparked news headlines around the globe. Summing up the public’s general feeling about the controversy, Brent Staples of the New York Times explained: “You can’t blame the pitchman for standing firm and insisting on his due.”

The public nature of the contract and its terms (including his hefty salary for a mere 15 hours of work each week, guaranteed first-class travel, and hefty pension payouts to Lee’s wife Joanie and daughter J.C.) led some comic book insiders to once again dredge up the argument regarding how the comic book artists and co-creators – most notably Jack Kirby – were treated by Marvel (and by extension Lee). Rehashing this notion and the idea that Lee attempted to capitalize off the success of the films turned some people against him. To critics, Lee got rich, while Kirby and others didn’t. The injustice had been done and they weren’t going to change their opinions, regardless of what Lee’s contract stipulated

In early 2005, after the judge presiding over the case ruled in Lee’s favor, he again appeared on 60 Minutes. “It was very emotional,” said Lee. “I guess what happened was I was really hurt. We had always had this great relationship, the company and me. I felt I was a part of it.” Despite the high profile nature of the lawsuit and its apparent newsworthiness, Marvel attempted to bury the settlement agreement with Lee in a quarterly earnings press release.

In April 2005, Marvel announced that it had settled with Lee, suggesting that the payoff cost the company $10 million. Of course, the idea that Lee had to sue the company that he spent his life working for and crisscrossing the globe promoting gave journalists the attention-grabbing headline they needed. And, while the settlement amount seemed grandiose, it was a pittance from the first Spider-Man film alone, which netted Marvel some $150 million in merchandising and licensing fees.

Despite the financial loss, the lawsuit resulted in an unexpected upside for Marvel. The settlement put in motion plans for the company to produce its own movies, a major shift in policy. Since the early 1960s, Marvel and its predecessor companies had licensed its superheroes to other production companies. Back then, the strategy allowed Marvel to outsource the risk involved with making television shows and films, but also severely hindered it from profiting from the creations. This move gave Marvel control, not only of the films themselves, but the future cable television and video products that would generate revenues.

Merrill Lynch & Co extended a $525 million credit line for Marvel to launch the venture (using limited rights to 10 Marvel characters as collateral), and Paramount Pictures signed an eight-year deal to distribute up to 10 films, including fronting marketing and advertising costs.

Interestingly, the details of the settlement between Lee and his lifelong employer shed light on suspect Hollywood accounting practices that film companies use to artificially reduce profitability. For example, for all the successes Marvel films had in the early 2000s, raking in some $2 billion in revenues between 2000-2005, Marvel’s cut for licensing equaled about $50 million. Despite his earlier contract with the company, Lee had received no royalties.

Although Lee received the settlement money and fences were eventually mended at Marvel, the episode is one of the stranger ones in Lee’s long career. In the long run, it transformed Marvel’s film strategy and helped it become a movie powerhouse.