Stan Lee: A Life Well-Lived -- Excelsior!

“Lee became Marvel madman, mouthpiece, and all-around maestro – the face of comic books for six decades. The man who wanted to pen the Great American Novel did so much more. Without question, Lee became one of the most important creative icons in contemporary American history.”

— Bob Batchelor, author, Stan Lee: The Man Behind Marvel

Read more5 Questions for Stan Lee Biographer and Cultural Historian Bob Batchelor

Why did you feel that Stan Lee needed a full-scale biography?

Ironically, when I interviewed self-professed Marvel and Lee fans, what I realized is that most didn’t know much about him (and much of what they thought they knew wasn’t the whole story). From this research I realized that my best bet would be to write a biography deeply steeped in archival research that provided an objective portrait that would give readers insight and analysis into Lee’s life and career. The research provided a deeply nuanced view of Lee’s life that I then conveyed to the reader. This commitment to the research and uncovering the man behind the myth is the driving force in the book.

In looking at a person’s life, especially one as long as Lee’s (he’ll turn 95 at the end of the year), context and historical analysis provides the depth necessary to create a compelling picture. So, for example, Lee grew up during the Great Depression and his family struggled mightily. I saw strains of this experience at play throughout his life that I then emphasized and discussed. As a cultural historian, my career is built around analyzing context and nuance, so that drive to uncover a person’s life within their times is at the heart of the narrative.

What would people find most surprising about Stan Lee’s career?

What many people don’t know about Stan Lee’s career is that he was the heart and soul of Marvel the publishing company, not just a writer as we might think of it today, toiling away in solitude. In addition to decades of writing scripts for comic books across many genres, like cowboy stories, monster yarns, or teen romances, Lee served as Art Director, head editor, and editorial manager, while also keeping an eye on publication and production details. The totality of his many roles, including budgeting for freelance writers and artists, necessitated that he keep his freelancers active, while also engaging them differently than other comic book publishers.

Lee worked with his artists, like the incomparable Jack Kirby and wonderful Steve Ditko, to co-create and produce the characters we all know and love today. The process that Lee created out of necessity because he had to keep the company efficient and profitable came to be known as the “Marvel Method.” It gave the artists more freedom in creating stories, since traditionally they worked off a written script. The Marvel Method blurred the definition of “creator,” but when Lee, Ditko, and others were creating superheroes, no one thought that they would become such a central facet of contemporary American culture. The line in the sand between who did what has become important to comic book aficionados and historians, but back then, they were just trying to make a living. So, if we want to fully understand Stan Lee and Marvel’s Silver Age successes, then we have to look at his myriad responsibilities in total.

How does your biography add to our understanding of Stan Lee?

Popular culture is so much more prevalent in today’s culture almost to the point of chaos. People feel pop culture – for better or worse – much more, since it is always blasting away at us. We feel that we “know” celebrities like Lee, because we engage with them much more than ever before. For example, Lee has 2.71 million Twitter followers.

Given that Lee is a mythic figure to many Marvel fans, I think what I’ve done well in the biography is present a full portrait of Lee as a publishing professional, film and television executive, cultural icon, and family man. One gets the sense of Lee as all these things when examining his archive at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. Lee is so much more than the much-anticipated film cameos and the biography attempts to reveal his family background, sorrows, triumphs, and successes in a way that hasn’t been done before.

What keeps you writing?

Regardless of the topic, storytelling is my foundation. Trying to figure out what makes a fictional character like Don Draper or Jay Gatsby tick versus an actual person like Lee or Bob Dylan, I am putting the storytelling pieces together to drive toward a better understanding. Phillip Sipiora, who teaches at the University of South Florida, is famous for saying that there aren’t really definitive answers, rather that the goal of the critic should be interrogation and analysis. I am not searching for the right answer, rather hoping to add to the body of knowledge by looking at a topic in a new or innovative way.

Throughout the process, I reserve time to just think deeply about the subject. I find that meditative time is essential. The fact that most people can no longer stand quiet, reflective time is one of the great tragedies to emerge from the web. I create basic outlines to guide my writing and thinking and constantly edit and revise. When I coach writers, I urge them to find a process that works for them, and then to hone it over time. My process fuels my work and enables me to work efficiently.

You’ve written or edited 29 books, what’s next?

In the near term, I think I have some things to say about early twentieth century American literature and its significance. Many people think they know the story, but there are still ideas to uncover there that are important to us 100 years later. I am also interested in working more in both film and radio. I’ll never give up writing and editing, but I would like to pursue some documentary projects and possibly create a radio show or some other way to reach larger audiences. Despite our current political climate, I think people still yearn for smart content, and I would like to fill that need.

Stan Lee in World War II: The Signal Corps Training Film Division

After Stan Lee enlisted in November 1942, his basic training took place at Fort Monmouth, a large base in New Jersey that housed the Signal Corps. The Signal Corps played a significant military role. Research played a prominent role in the division and on the base. Several years earlier, researchers had developed radar there and the all-important handheld walkie-talkie. In the ensuing years, they would learn to bounce radio waves off the moon.[i]

At Fort Monmouth, Lee learned how to string communications lines and also repair them, which he thought would lead to active combat duty overseas. Army strategists realized that wars were often determined by infrastructure, so the Signal Corps played an important role in modern warfare keeping communications flowing. Even drawing in numerous talented, intelligent candidates, the Signal Corps could barely keep up with war demands, which led to additional training centers opening at Camp Crowder, Missouri, and on the West Coast at Camp Kohler, near Sacramento, California.

On base, Lee also performed the everyday tasks that all soldiers carried out, like patrolling the perimeter and watching for enemy ships or planes mounting a surprise attack during the cold New Jersey winter. Lee claimed that the frigid wind whipping off the Atlantic nearly froze him to the core.

The oceanfront duty ended, however, when Lee’s superior officers realized that he worked as a writer and comic book editor. They assigned him to the Training Film Division, coincidentally based in Astoria, Queens. He joined eight other artists, filmmakers, and writers to create a range of public relations pieces, propaganda tools, and information-sharing documents. His ability to write scripts earned him the transfer. Like countless military men, Lee played a supporting role. By mid-1943, the Corps’ consisted of 27,000 officers and 287,000 enlisted men, backed by another 50,000 civilians who worked alongside them.

The converted space that the Army purchased at 35th Avenue and 35th Street in Astoria housed the Signal Corps Photographic Center, the home of the official photographers and filmmakers to support the war effort. Col. Melvin E. Gillette commanded the unit, also his role at Fort Monmouth Film Production Laboratory before the Army bought the Queens facility in February 1942, some nine months before Lee enlisted. Under Gillette’s watchful eye, the old movie studio, originally built in 1919, underwent extensive renovation and updating, essentially having equipment that was the equivalent of any major film production company in Hollywood.

Gillette and Army officials realized that the military needed unprecedented numbers of training films and aids to prepare recruits from all over the country and with varying education levels. There would also be highly-sensitive and classified material that required full Army control over the film process, from scripting through filming and then later in storage. The facility opened in May 1942 and quickly became an operational headquarters for the entire film and photography effort supporting the war.

The Photographic Center at Astoria, Long Island, was a large, imposing building from the outside. A line of grand columns protected its front entrance, flanked by rows of tall, narrow windows. Inside the Army built the largest soundstage on the East Coast, enabling the filmmakers to recreate or model just about any type of military setting.

Lee found an avenue into the small group of scribes. “I wrote training films, I wrote film scripts, I did posters, I wrote instructional manuals,” Lee recalled. “I was one of the great teachers of our time!”[ii] The illustrious division included many famous or soon-to-be-famous individuals, from three-time Academy-award winning director Frank Capra and New Yorker cartoonist Charles Addams to a children’s book writer and illustrator named Theodor Geisel. The world already knew Geisel by his famous penname “Dr. Seuss.”

Although Lee often jokes about his World War II service, even a passing examination of the work he and the other creative professionals performed for the nation reveals the significance of the division across multiple areas. According to the official history of the Signal Corps effort during World War II:

Even before Pearl Harbor the demand for training films was paralleling the growth of the armed forces. After war came the rate of demand rose faster than the rate of growth of the Army, because mass training of large numbers of men could be accomplished most effectively through the medium of films. For fiscal year 1942 the sum of $4,928,810 was appropriated for Army Pictorial Service, of which $1,784,894 was for motion picture production and $1,304,710 for motion picture distribution, chiefly of training films. More than four times that sum, $20,382,210, was appropriated for the next fiscal year, 1943, and half went for training films and for training of officer and enlisted personnel in photographic specialist courses.[iii]

The stories that must have floated around that room during downtime or breaks!

[i] During the time Lee was stationed at Fort Monmouth, Julius Rosenberg carried out a clandestine mission spying for Russia. He also recruited scientists and engineers from the base into the spy ring he led in New Jersey and funneled thousands of pages of top-secret documents to his Russian handlers. In 1953, Rosenberg and his wife Ethel were arrested, convicted, and executed.

[ii] Stan Lee, interview by Steven Mackenzie, “Stan Lee Interview: ‘The World Always Needs Heroes,’” The Big Issue, January 18, 2016, http://www.bigissue.com/features/interviews/6153/stan-lee-interview-the-world-always-needs-heroes.

[iii] Thompson, George Raynor, Dixie R. Harris, et al. The Signal Corps: The Test (December 1941 to July 1943). (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1957), 419.

The Black Knight Debuts in 1955

“Strike, black blade! The Black Knight challenges Modred the Evil!”

Mixing the legendary tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table with elements from superhero lore, Stan Lee and his favorite artist Joe Maneely cocreated The Black Knight for Atlas Comics, debuting in May 1955.

Lee and Maneely took a risk in bringing out the new hero, despite the enduring popularity of King Arthur for centuries. Superhero comic books were basically out of favor in the 1950s, thanks to the ravings of lunatic psychiatrist Frederic Wertham and countless adults who believed his diatribes against the industry, particularly that reading comic books paved the path to juvenile delinquency.

Wertham’s backlash had sent the publishing industry reeling, forcing many companies into bankruptcy. If you didn’t work at a publisher named DC or have characters like Superman and Batman, then turning to other genres proved the only way to stay afloat.

The artistic duo’s creation featured a powerful, armored hero who hid behind a secret identity (the meek Sir Percy of Scandia) so that he could thwart wrongdoers. The Black Knight worked with famed magician Merlin to protect and defend King Arthur's Camelot from the schemes of Modred the Evil.

In the post-Wertham environment, publisher Martin Goodman and editor Lee fiddled with the comic book lineup, attempting to find the right mix that readers would buy. At that time, however, superheroes were out at Atlas. Even the mighty Sub-Mariner would be cancelled in October 1955 with Sub-Mariner #45.

Despite how much the artistic duo of Lee and Maneely loved the Black Knight character, the series only lasted five issues, folding with the April 1956 cover dated copy. Instead, the company moved to cowboy comics, suspense series, and Hollywood tie-ins in an attempt to wrangle the fickle marketplace. Atlas' place on the newspaper stands would feature titles like World Of Fantasy, World of Mystery, and old favorites like Millie The Model.

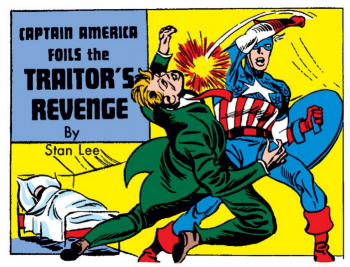

Stan Lee’s First Publication – Captain America Comics #3 (1941)

Joe Simon needed copy and he needed it fast!

The Timely Comics editorial director and his coworker and friend Jack Kirby were hard at work on the hit they had recently launched – the red, white, and blue hero Captain America. Readers loved the character and Simon and Kirby scrambled to meet the demand.

The Captain America duo brought in some freelancers to keep up. Then they threw some odd copy-filler stories to their young apprentice/office boy Stanley Lieber as a kind of test run to see if the kid had any talent. He had been asking to write and the short story would be his on-the-job audition.

The throwaway story that Simon and Kirby had the teenager write for Captain America Comics #3 (May 1941) was titled: “Captain America Foils the Traitor’s Revenge.” The story also launched Lieber’s new identity as “Stan Lee,” the pseudonym he adopted in hopes of saving his real name for the future novel he might write.

Given the publication schedule, the latest the teen could have written the story is around February 1941, but he probably wrote it earlier. The date is important, because it speaks to Lieber’s career development. If he joined the company in late 1939, just after Kirby and Simon and when they were hard at work in developing Captain America, then there probably wasn’t much writing for him to do. However, if the more likely time frame of late 1940 is accepted, then Lieber was put to work as a writer fairly quickly, probably because of the chaos Simon and Kirby faced in prepping issues of Captain America and their other early creations, as well as editing and overseeing the Human Torch and Sub-Mariner efforts.

Lee later acknowledged in his autobiography that the two-page story was just a fill-in so that the comic book could “qualify for the post office’s cheap magazine rate.” He also admitted, “Nobody ever took the time to read them, but I didn’t care. I had become a published author. I was a pro!” Simon appreciated the teen’s enthusiasm and his diligence in attacking the assignment.

An action shot of Captain America knocking a man silly accompanied Lieber’s first publication for Simon and Kirby. The story – essentially two pages of solid text – arrived sandwiched between a Captain America tale about a demonic killer on the loose in Hollywood and another featuring a giant Nazi strongman and another murderer who kills people when dressed up in a butterfly costume. “It gave me a feeling of grandeur,” Lee recalled at the 1975 San Diego Comic-Con.

While many readers may have overlooked the text at the time, its cadence and style is a rough version of the mix of bravado, high-spirited language, and witty wordplay that marked the young man’s writing later in his career.

Lou Haines, the story’s villain, is sufficiently evil, although we never do find out what he did to earn the “traitor” moniker. In typical Lee fashion, the villain snarls at Colonel Stevens, the base commander: “But let me warn you now, you ain’t seen the last of me! I’ll get even somehow. Mark my words, you’ll pay for this!”

In hand-to-hand combat with the evildoer, Captain America lands a crippling blow, just as the reader thinks the hero may be doomed. “No human being could have stood that blow,” the teen wrote. “Haines instantly relaxed his grip and sank to the floor – unconscious!” (Captain America Comics #3, p. 37) The next day when the colonel asked Steve Rogers if he heard anything the night before, Rogers claims that he slept through the hullabaloo. Stevens, Rogers, and sidekick Bucky shared in a hearty laugh.

The “Traitor” story certainly doesn’t exude Lee’s later confidence and knowing wink at the reader, but it clearly demonstrates his blossoming understanding of audience, style, and pace.

Both “Stan Lee” and a career were launched!

Stan Lee Sues Marvel…And Wins!

In a tale filled with greed, envy, unfulfilled promises, and years of legal scheming, Marvel announced a financial settlement on April 28, 2005, with its most famous employee – comic book legend Stan Lee.

Filed under the heading, “Things No One Ever Expected,” Lee had sued Marvel three years earlier for not fulfilling the terms of his employment contract. The subsequent legal maneuvering created a tense situation for Lee and a public relations headache for the company he had helped build.

The beguiling battle began in late October 2002, when the popular CBS news program 60 Minutes II aired a segment about the state of comic books and the tremendous popularity of superhero films. The report also examined Lee’s potential skirmish with Marvel regarding language in his contract, specifically certain payments Lee justly deserved based on the surging box office returns of Marvel films after decades of mediocre efforts and failed attempts at bringing the company’s superheroes to the screen.

The new program painted Marvel in an evil light – a greedy corporation making insane amounts of money off the backs of its writers and artists. Lee’s 1998 contract seemed straightforward, but when it was inked no one expected the future to include such wildly successful films – X-Men (2000) earned nearly $300 million worldwide, while Spider-Man (2002) became a global phenomenon, drawing some $821 million.

60 Minutes II correspondent Bob Simon, using a bit of spicy language that seemed uncharacteristic for the venerable CBS show, actually asked Lee if he felt “screwed” by Marvel. Lee toned down his usual bombast though and displayed remorse for having to sue his employer, a situation that he explained “I try not to think of it.” As a result, many Marvel fans sided with Lee in the dispute.

Mere days after the segment aired, Lee sued Marvel for not honoring a stipulation that promised to pay him 10 percent of the profits from Marvel Enterprise film and television productions. Despite his $1 million annual salary as chairman emeritus, Lee’s attorney’s argued that the provision be honored. The grand battle between Marvel and its most famous employee shocked observers and sparked news headlines around the globe. Summing up the public’s general feeling about the controversy, Brent Staples of the New York Times explained: “You can’t blame the pitchman for standing firm and insisting on his due.”

The public nature of the contract and its terms (including his hefty salary for a mere 15 hours of work each week, guaranteed first-class travel, and hefty pension payouts to Lee’s wife Joanie and daughter J.C.) led some comic book insiders to once again dredge up the argument regarding how the comic book artists and co-creators – most notably Jack Kirby – were treated by Marvel (and by extension Lee). Rehashing this notion and the idea that Lee attempted to capitalize off the success of the films turned some people against him. To critics, Lee got rich, while Kirby and others didn’t. The injustice had been done and they weren’t going to change their opinions, regardless of what Lee’s contract stipulated

In early 2005, after the judge presiding over the case ruled in Lee’s favor, he again appeared on 60 Minutes. “It was very emotional,” said Lee. “I guess what happened was I was really hurt. We had always had this great relationship, the company and me. I felt I was a part of it.” Despite the high profile nature of the lawsuit and its apparent newsworthiness, Marvel attempted to bury the settlement agreement with Lee in a quarterly earnings press release.

In April 2005, Marvel announced that it had settled with Lee, suggesting that the payoff cost the company $10 million. Of course, the idea that Lee had to sue the company that he spent his life working for and crisscrossing the globe promoting gave journalists the attention-grabbing headline they needed. And, while the settlement amount seemed grandiose, it was a pittance from the first Spider-Man film alone, which netted Marvel some $150 million in merchandising and licensing fees.

Despite the financial loss, the lawsuit resulted in an unexpected upside for Marvel. The settlement put in motion plans for the company to produce its own movies, a major shift in policy. Since the early 1960s, Marvel and its predecessor companies had licensed its superheroes to other production companies. Back then, the strategy allowed Marvel to outsource the risk involved with making television shows and films, but also severely hindered it from profiting from the creations. This move gave Marvel control, not only of the films themselves, but the future cable television and video products that would generate revenues.

Merrill Lynch & Co extended a $525 million credit line for Marvel to launch the venture (using limited rights to 10 Marvel characters as collateral), and Paramount Pictures signed an eight-year deal to distribute up to 10 films, including fronting marketing and advertising costs.

Interestingly, the details of the settlement between Lee and his lifelong employer shed light on suspect Hollywood accounting practices that film companies use to artificially reduce profitability. For example, for all the successes Marvel films had in the early 2000s, raking in some $2 billion in revenues between 2000-2005, Marvel’s cut for licensing equaled about $50 million. Despite his earlier contract with the company, Lee had received no royalties.

Although Lee received the settlement money and fences were eventually mended at Marvel, the episode is one of the stranger ones in Lee’s long career. In the long run, it transformed Marvel’s film strategy and helped it become a movie powerhouse.