My Personal Journey: Marvel Comics, Electric Company, and Reading

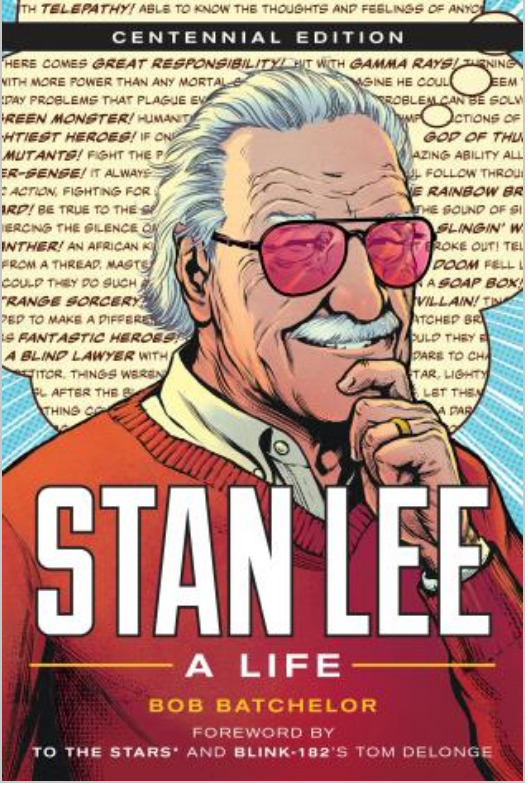

Stan Lee: A Life by Bob Batchelor, celebrating the 100-year history of the iconic creative force!

My criteria for who or what to write about as a biographer and cultural historian is a mix of a.) personal interest, and b.) impact the person or group has had on culture. Clearly, Stan Lee fits.

When thinking about possible topics, I wanted to find an iconic figure whose life and work had influenced countless millions of people. There are many people who fit this description, but back in 2014 and 2015 when I was thinking about who, the possibilities were not endless. Many figures had biographies written about them or had covered their own territory via autobiography or memoir. Others I didn’t find interesting enough — personally — to want to spend five or more years with: from research to writing to publication to marketing to more marketing, etc. Taking on a biography is a LONG process of essentially getting inside another human being’s skin (and letting them in yours in some strange way), so commitment is fundamental.

When Stephen Ryan, then editor at Rowman & Littlefield, suggested Stan, he seemed a natural subject to explore in a full-scale biography. And, of course, I am a lifelong Marvel and Lee fan, so I felt I had some insight into his life at the outset.

The popularity of the Marvel film universe had rekindled Lee’s global popularity. Ironically, though, when I interviewed self-professed Marvel and Lee fans, what I realized is that most didn’t know much about him (and much of what they thought they knew wasn’t the whole story).

What could I add to the body of knowledge about Lee? I figured my best bet would be to write a biography deeply steeped in archival research that provided an objective portrait that would give readers insight and analysis into Lee’s life and career. Multi-archival research had been the training I received as a historian, so I went to the Stan Lee Archives at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. I searched out information at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, a wonderful space at Ohio State University.

The research provided a deeply nuanced view of Lee’s work that I then conveyed to the reader. This commitment to the research and uncovering the “man behind the myth” became the driving force of the initial book, published in late 2017, titled Stan Lee: The Man Behind Marvel.

In looking at a person’s life, especially one as long as Lee’s, context and historical analysis provides the depth necessary to create a compelling picture. For example, Lee grew up during the Great Depression and his family struggled mightily. I saw strains of this experience at play throughout his life that I then emphasized and discussed. As a cultural historian, my career is built around analyzing context and nuance, so that drive to uncover a person’s life within their times is at the heart of the narrative.

Another important element in writing about Lee was to really give a thorough going-over of his life and experiences as an editor of comic books. Stripping away the film cameos, the fame, and the self-created “comic book man” persona, I felt it was Lee’s work as an editor, art director, production manager, writer, and boss that had not been fully explored.

Stan Lee greeting the adoring crowd at a comic book convention

What I Hoped to Accomplish

In the initial biography and the two that followed — Stan Lee: A Life and Stan Lee: The Man Behind Marvel, Young Adult Edition — what the reader gets is multi-archival research and deep engagement with contemporary American history. Basically, I wanted to write a biography that is based on archival research, but written for general fans and readers. The books explore Lee’s rise as a kind of fulfillment of the American dream, from near-poverty in Depression-era New York City to the comic book industry’s iconic visionary, a man who created (with talented artists) many of history’s most legendary characters.

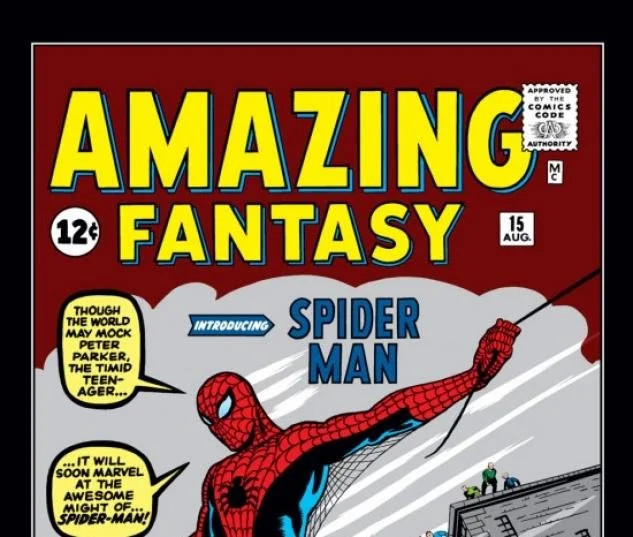

The books look at how Lee capitalized on natural talent and hard work to become the editor of Marvel Comics as a teenager. After toiling in the industry for decades, Lee threw caution to the wind and went for broke, co-creating the Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, Hulk, Iron Man, the X-Men, the Avengers, and others in a creative flurry that revolutionized comic books for generations of readers. Marvel superheroes became a central part of pop culture, from people who began collecting comics to the company’s innovative merchandising, from superhero action figures to the ever-present Spider-Man lunchbox.

My biographies of Lee examine many of his most beloved works, including the 1960s comics that transformed Marvel from a second-rate company to a legendary publisher. What I hoped to show is that Lee took risks to bring the characters to life. Of course, he didn’t do it alone, and the battle over who did what and when has led comic book historians and others to draw battle lines that are hard and fast. What I wanted to demonstrate, though, was that it took Lee’s tireless efforts to make comic books and superheroes part of mainstream culture.

The biographies not only reveal why Lee developed into such a central figure in American entertainment history, but explores the cultural significance of comic books and how the superhero genre reflects ideas central to the American experience.

Personal Journey

As mentioned earlier, personal interest is critical for a biographer. If you believe eminent author Jerome Charyn, who exclaims, “Every book is really about me,” then you’ll understand the connection between subject and writer. Essentially, an author is asking, “From my lived experience and mental map, what can I add to this story that is uniquely from my perspective?” This thought is often discussed in the work of Carl Rollyson, in my opinion the “dean” of biography for his work as a biographer and biography theorist.

My personal experience certainly led to my interest in writing about Lee and Marvel — now stretching to more than nine years of research, writing, talking about, and thinking about the iconic figure. But, my personal interest dwarfs my professional interest.

At around four years-old, I taught myself to read so that I could “understand” Spider-Man comic books. I remember really needing to make sense of the words, which struck me so much more than the images and art. And, this later played a role in my thinking as I met and talked to artists and people who love art over text in comic books. I think that some people are “words” people and some are “art.” I am clearly about the words, so this ability to read comic books meant so much more to me than the pictures. I never thought twice about who drew comic books, but I did attempt to make a connection between the words and how they played out on the page.

Another perspective came from watching the Electric Company on PBS (back when there were literally only a handful of channels to choose from). “Spidey’s Super Stories” were live-action skits featuring the web-slinger and I lived for those spots. The vignettes debuted in 1974, so the timeline (when I look back on it now), fits with my Gen X youth.

This is the skeleton of my five decades-plus relationship with Stan Lee, Marvel, and particularly Spider-Man. I am so proud of the three Lee biographies and believe strongly that Stan himself would be happy to know they exist. And, who know…maybe there is another Lee biography or book with Stan as a central figure still left in me…as Rollyson says, “The answer to one biography is another biography.”